60 Years of Vertigo

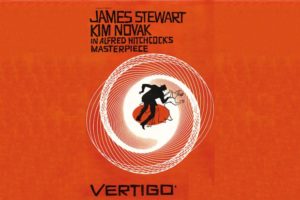

The 60th anniversary of the cinematic release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo takes place in May 2018 and we look back upon this psychological thriller which has been described in various critical quarters as the director’s masterpiece. Based upon the 1954 crime novel D’entre les morts (From Among the Dead) by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, Vertigo is a riveting tale concerning the psychological obsession which takes hold when a retired San Francisco detective is asked to shadow the wife of an old college friend. According to the 1996 documentary Obsessed with Vertigo (narrated by Roddy McDowall), Hitchcock first became interested in the Golden Gate City as a filming location when he visited there whilst promoting the release of 1951’s Strangers on a Train. The director was overheard to remark that San Francisco seemed like a city which would lend itself well to a detective thriller and, so, he made good upon his words when principal photography for Vertigo began there in September 1957. The opening scene of Vertigo – the rooftop chase scene involving James Stewart’s John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson – leaves us in no doubt as to where we are in spite of the nighttime setting. There is a glimpse of an iconic bridge and the very familiar sound of a foghorn in the background. The sequence reaches its climax when the police officer falls to his death as he tries to assist Scottie who has suddenly become afflicted with acrophobia and vertigo. The scene allows Hitchcock the opportunity to introduce the famous dolly-out/zoom-in camera effect for the very first time in order to visually convey Scottie’s perceptual trauma. The shot has become widely known as the ‘Vertigo effect’ and remains one of the master’s most indelible technical moments.

The scene which follows this dramatic opening is one of narrative exposition, but, in typical Hitchcock fashion, there are subtexts to be garnered and hidden meanings lurking just below the surface. Lounging in the studio apartment of his close friend Marjorie ‘Midge’ Wood (Barbara Bel Geddes), Scottie is now retired from the force and contemplating his life of leisure. On a physical level, he is almost entirely recovered from the incident, but the emotional scars remain below the surface. When he jokes with Midge about them being briefly engaged whilst in college, Bel Geddes’s subtle reaction suggests at how she may still be romantically keen on him. Of even greater import perhaps is her look of disappointment when he admonishes her ever so slightly for being ‘motherly.’ Scottie’s acrophobia and vertigo return with a vengeance at the conclusion of this scene as he tries to prove he can overcome them. We, the audience, are left in little doubt as to the exact nature of his condition. The sensation causes Scottie to lose his balance and footing. The obsession which will engulf him will similarly cause a loss of proportion and reason. The mystery begins properly when Scottie is employed by an old college friend named Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) to follow his wife Madeleine. Ferguson is reluctant to do so (‘This isn’t my line’) and is not exactly convinced by Elster’s story regarding his wife being possessed by a dead person. But he agrees to have a drink at Ernie’s restaurant later that evening where Elster and his wife will be dining.

This is one of the most memorable scenes in the film as it introduces Kim Novak and also establishes the first hint of obsession. Bernard Herrmann’s masterly score plays on the soundtrack as Novak and Helmore approach the bar where Scottie is having a drink. A side profile of Novak set against the backdrop of the restaurant appears to be enough to entice the previously hesitant Scottie. The truth which unfolds later in the film will reveal this to be a ruse on the part of Elster. The then 24-year-old Novak is truly radiant on-screen and it’s entirely understandable why she is so captivating to Scottie’s eyes. The exterior scenes which follow involve Scottie tailing her in his car. Madeleine leads him to a store, where she purchases a bouquet of flowers, followed by a church and a cemetery. The grave she stands over so reverentially bears the name of one Carlotta Valdes. In an art gallery (The Palace of the Legion of Honor), the young woman sits entirely fixated by a portrait of the aforementioned Carlotta. The scene which follows this is one which has always puzzled me as a viewer, but which, I suspect, is something of a tease on the part of Hitchcock. Entering an old boarding house called the McKittrick Hotel, Madeleine is seen opening a bedroom window and gazing out on the street below. When Scottie pursues her inside however, the soft-spoken landlady (Ellen Corby) claims that the woman has not been there all day. ‘She just comes to sit two or three times a week’ she tells the baffled detective before showing him the room which indeed is empty. An intentional trick on the part of the master, or some element of the supernatural? The former I would have to suggest given the revelations which come to light later in the film.

One of Vertigo’s most curious scenes occurs when Midge takes Scottie to meet Pop Leibel (Konstantin Shayne) at the Argosy Book Store. An acknowledged authority on the small history of San Francisco, Pop Leibel offers some further elucidation on the tragic history of Carlotta Valdes. As he relays this, and the full extent of Carlotta’s unfortunate life is explained, I would direct the first-time viewer to pay heed to the use of lighting in the scene and how it drops appreciably. ‘She became the sad Carlotta…and the mad Carlotta’ he reflects as the light inside the store is lowered almost entirely. Leibel’s comments in this regard are confirmed by Elster himself when he tells Scottie that Carlotta was Madeleine’s great-grandmother and the McKittrick Hotel the former Valdes home. ‘She’s no longer my wife’ he solemnly declares as Scottie attempts to bring the story back to a basis in reality. The pursuit continues the next day – presumably – as Madeleine parks her car at the iconic location of Fort Point at the southern side of the Golden Gate at the entrance to San Francisco Bay. One of Vertigo’s most seminal moments takes place when she throws herself into the bay and is rescued by Scottie. When she awakens later that evening at Scottie’s house, Madeleine claims to have no memory of the incident. The first physical manifestation of his attraction towards her is captured quite simply when he touches her hand for the briefest of moments. The false sense of the macabre is returned to when Elster phones and informs Scottie that Madeleine is 26 and that Carlotta Valdes committed suicide when she was the same age. Madeleine slips away while Scottie is taking this call and, as she departs, Midge is seen pulling up outside Scottie’s home. ‘Was it a ghost? Was it fun?’ she says to herself as she looks across the street at Scottie who, in turn, is watching as Madeleine’s car passes away. The scene suggests an unhealthy level of preoccupation which is not solely confined to Scottie. Midge too has her compulsions and jealousies and, quite evidently, she does not take kindly to the notion of his being attracted to this beautiful woman.

Scottie continues his assignment on the very next day and is highly surprised when Madeleine returns to his house. ‘I remembered Coit Tower’ she tells him as she explains the reason for her visit. ‘It’s the first time I’ve been grateful for Coit Tower’ he replies as he accepts her thank-you note. On the premise that they should ‘wander’ together instead of alone, Scottie accompanies her to the site of the redwood trees in Muir Woods National Monument. For the record, the scene in question wasn’t actually shot in Muir Woods, but rather in Big Basin Redwoods State Park which is located in Santa Cruz County. As shot by cinematographer Robert Burks (The Birds, Strangers on a Train, North By Northwest), the scene has a suitably haunting quality about it as the supposedly possessed Madeleine reflects on the nature of her own mortal condition compared to the trees (Sequoioideae) which can live for thousands of years – ‘I don’t like it…knowing I have to die.’ The coastal region where Scottie and Madeleine share their first intimate moment is that of Cypress Point which is located along the 17-mile drive near Pebble Beach. ‘If I could just find the key…the beginning…and put it together’ he says as his sense of duty and devotion towards the troubled woman continues to grow. The dramatic splash of a wave punctuates the warm embrace and kiss which takes place between Scottie and Madeleine. ‘I’ve got you’ he tells her in more than a hint of his desire to totally possess her. Scottie’s infatuation in truth knows no bounds at this point. He cares little for Elster any longer and the parameters of his task have changed quite markedly. Madeleine is now his to protect, her love is his to secure.

The nature and extent of Scottie’s passion and protectiveness towards Madeleine is emphasised in the scene whereby the envious Midge plays a cruel joke on him. Midge’s portrait of herself mimics the one of Carlotta in the Palace of the Legion of Honor, but only serves to elicit a negative response from the unimpressed Scottie. When he departs, Midge chides herself by tugging at her hair and destroying the painting – ‘Stupid! Stupid!’ she repeats. A distraught Madeleine appears on Scottie’s doorstep and describes in more detail the recurring nightmare she has been having in which she foresees her own death. The location which she outlines is recognised by Scottie as Mission San Juan Bautista and he takes her there that same day in the hope/expectation that this will break her free of her supposed possession. The mission in question is located in San Benito County and was suggested to Hitchcock as a suitable filming location by the associate producer Herbert Coleman’s daughter. The famous bell tower which appears in the film was not real as the actual steeple had been demolished following a fire; scale models, matte paintings and trick photography were employed to create this illusion. The tower’s staircase was constructed in the studio. Attempting to convince Madeleine that she can escape the trappings of the past and her own tortured soul, Scottie calls upon all his powers of persuasion – ‘There’s an answer for everything…Try for me…No one possesses you, you’re safe.’ Madeleine insists on going into the church alone and races up the bell tower. Scottie follows, but his acrophobia and vertigo (presented again by the famous camera shot) prevents him from stopping her. Madeleine falls to her death and Scottie freezes on the staircase. There is a particularly memorable overhead shot of the church which Hitchcock uses as a distressed Scottie exits the building and leaves the scene of the apparent suicide. It’s reminiscent of a similar one the director employs at the UN Building in New York in 1959’s North by Northwest. The inquisition into Madeleine’s death which follows is not particularly kind to Scottie and finds that, once again, he was unable to act when another individual was in peril owing to his acrophobia. A serenely philosophical and forgiving Gavin Elster tells Scottie that he is leaving San Francisco and remarks that ‘You and I know who killed Madeleine.’

Some of Vertigo’s most bleakest moments follow as a guilt-ridden Scottie descends into clinical depression. He is committed to a sanatorium and appears almost in a catatonic state when Midge comes to visit. Scottie’s condition is referred to as ‘acute melancholia’ and Midge tries in vain to reach him as a piece of music by Mozart plays in the background. Scottie’s doctor informs her that it is impossible to know how long he may remain in this state. Dubious regarding the merits of using music as a means of therapy, Midge informs him that Scottie was in love with Madeleine and matter-of-factly adds ‘I can give you another complication, he still is.’ Midge departs the sanatorium and this is the very last time we see her character in the film. It’s an exit which is tinged with complete sadness and no small amount of hopelessness. The man she loves is beyond her reach; her particular fixation on him appears to have reached its hollow conclusion.

The film moves forward in time then, but the exact passage is never specifically defined. Exterior scenes in San Francisco establish that Scottie has left the sanatorium, but his memories and longing for Madeleine still remain. There are three scenes in quick succession which emphasise this – in each one Scottie mistakes a woman for his beloved – the first occurs outside Madeleine’s former apartment building, the second in Ernie’s and the third in the Palace of the Legion of Honor. On a street in the city, Scottie randomly spots a pretty brunette who more than bears a strong resemblance to Madeleine. Following her to her room at the Empire Hotel, he invites her out for dinner. The young woman, who identifies herself as Judy Barton from Salina, Kansas, reluctantly accepts. One of Vertigo’s most discussed scenes plays out next as we learn that the woman in question is in fact the same person who impersonated Gavin Elster’s wife. A flashback scene to the bell tower at the mission establishes this and a voiceover delivered by Kim Novak’s character (as she pens a letter of admission to Scottie) explains how Elster had plotted to kill his spouse and exploited Scottie’s weakness for heights as a means of carrying this out (‘I was the tool. You were the victim of Gavin Elster’s plan to kill his wife…he knew of your illness…I made the mistake, I fell in love’). The scene is very significant from a narrative perspective as it informs us the audience of the real truth whilst, of course, leaving Scottie entirely oblivious to these facts. The decision to reveal this crucial backstory was not easily reached and Hitchcock, by all accounts, deliberated on it for some time. The letter writing scene involving Judy’s character was re-inserted in the final film following studio pressure apparently, but I think the revelation works well as it serves to highlight Judy’s subsequent moral dilemma when Scottie attempts to re-imagine her physically as Madeleine. In the original novel by Boileau and Narcejac, the truth of Judy’s involvement in Madeleine’s demise was not disclosed until the final act. Here, in the film, it is foregrounded and adds to the dramatic tension which the viewer experiences.

Continuing his pattern of returning to places which remind him of Madeleine, Scottie takes Judy out to dinner at Ernie’s. Later on that evening – back at her hotel – he offers to take care of her. ‘Why? Because I remind you of her?’ Judy responds. Again, she agrees to this with a degree of hesitation, but with little serious objection. The obsessive bent of Scottie’s mind – and Vertigo’s foremost theme – reaches fever pitch as he seeks to make Judy over so that she will resemble Madeleine in manner and appearance. First he begins with her clothes insisting that he purchase the same grey suit that Madeleine wore as well as the evening dress he saw her in at Ernie’s. Legendary costume designer Edith Head had chosen the colour of grey for Madeleine’s suit as this was not typical of a blonde’s colour and, so, would serve to be jarring in effect. ‘The gentleman seems to know what he wants’ the shop manager remarks as Scottie describes the clothes he wants for Judy. For her part – and unbeknownst to Scottie at this point – Judy is perfectly aware of what his motivation entails. ‘Couldn’t you just like me the way I am?’ she asks before he then requests that she change the colour of her hair. Critics have commented on this make-over of Judy as being tantamount to male aggression and symptomatic of the objectification of the female body. One could argue that such themes were further extended in Hitchcock’s Marnie (1964) which culminated with the infamous rape scene. There’s no such violation here, but Scottie’s demands certainly do have a forceful and even demeaning aspect to them – ‘Judy! Please! It can’t matter to you!’ Based on the promise that he will love her if she will allow him to change her, Judy agrees to undergo the physical transformation desired by Scottie – this chiefly involves her hair being dyed blonde. When she returns to the Empire Hotel that evening, wearing the grey suit, Scottie is still unsatisfied as he asks that her hair be pinned back from her face. My own personal favourite moment in Vertigo occurs after Judy emerges from the bathroom as Madeleine and the two kiss and embrace. This is the Scene d’Amour – as it is described in Bernard Herrmann’s score – and it involves the camera circling the couple as they share a deeply passionate moment. At a key moment, Scottie looks around him and imagines that he is back in the stables at the Mission San Juan Bautista just prior to Madeleine’s death. The implication of this particular shot is open to interpretation – Does he realise that the past can never be completely recaptured? Is there a tacit acceptance of this on his part as she kisses Judy once again? Or is there the suggestion on Hitchcock’s part that Scottie’s obsession can never be entirely sated? In any event, it’s an utterly masterly shot by a director who was at the very height of his powers.

The mood soon changes, and any hopes of a happy ending dissipate, as Judy makes the critical error of putting on the necklace which had purportedly belonged to Carlotta Valdes. Spotting this almost immediately in the mirror, Scottie suggests that they go somewhere out of town for dinner, perhaps down the peninsula in his words. Judy’s suspicions are sparked as they drive in the direction of Mission San Juan Bautista (‘We’re going awfully far’) and her fears are further heightened by Scottie’s quietly resolute demeanour as they traverse a tree-lined road in the country – ‘One final thing I have to do, and then I’ll be free of the past.’ Scottie takes Judy into the same church which she had entered as Madeleine and up the same bell tower on the premise that he now wishes to free himself of the past in – ironically – the same way he had sought to free Madeleine of her supposed troubled past apropos Carlotta Valdes – ‘One doesn’t always get a second chance. I want to stop being haunted.’ Half way up the staircase of the steeple, Scottie reveals his recently acquired knowledge of the truth – ‘This was as far as I could get, but you went on’ he tells her. Rage now supplants obsession as he turns on Judy for her part in the murder of Gavin Elster’s wife – ‘I was the made-to-order witness!’ Protesting her innocence as regards Elster’s true intentions towards his wife, Judy seeks to convince Scottie that she loves him in spite of her previous deceptions – ‘I loved you so. I walked into danger and let you change me because I loved you and I wanted you.’ But – with his ideal of Madeleine now shattered – Scottie appears to resist the notion that they can ever have a future together – ‘It’s too late, there’s no bringing her back.’ Whether or not he would acquiesce to the compromise suggested by the tainted Judy becomes quite immaterial as a shadowy figure rises from the trapdoor of the bell tower. Startled by this almost spectral apparition (which turns out to be a nun from the mission), Judy falls to her death in a similar manner as Elster’s wife. As the sister raises the alarm by ringing the bell, a desolate Scottie stands out on the ledge and extends his arms. Some viewers and critics believe that this is a clear indication on the director’s part that Scottie has been jolted out of his fear of heights and the attendant vertigo which have been plaguing him (bear in mind how Midge had earlier told Scottie that perhaps only an immense shock would cure him of his phobia). This may well be the case, but I personally think that the gesture of extending his arms suggests the utter hopelessness of Scottie’s position now. With nowhere to go, and no one to turn to (Midge, remember, has not appeared or even been mentioned in this final third of the film), Scottie would appear to be a lost man in this final iconic shot. Bereft of purpose – even of obsession at this stage – he seems to grasp the wretchedness of his own position. The Madeleine of his ideals – a person who, in truth, was a fabrication to begin with – has long since vanished and now the woman who projected this construct so deftly has fallen to her untimely death. Devoid now of even infatuation, Scottie takes one last look from the ledge and ponders the absolute morass that his life has once again become. This is in keeping with the spiral motif which is ever-present from Vertigo’s opening titles. At the film’s end, Scottie has returned to an unenviable place and – one would have to imagine – an emotional state that is beyond the mere problematic. A man more sinned against than sinning perhaps, he nonetheless has played a significant part in his own moral downfall.

Released in the early summer of 1958, Vertigo was received with more than a few mixed reviews at the time and it did not seem destined to go down as one of Hitchcock’s classics. Many cited inherent problems with the film’s pacing and the themes which it presented. The mystery, which is solved from the audience’s perspective with a third of the film remaining, jarred with a lot of viewers and critics. The obsession which Stewart’s character is consumed by and the lengths he asks Novak’s character to go to in order to satisfy this were problematic for many. It was difficult for audiences to identify with these characters; even more of a stretch to sympathise with their situations. The male lead was a man insisting on the need to re-play a deep and disturbing fixation he had on a woman he was supposed to be protecting. Kim Novak’s character, on the other hand, was essentially an impostor. The fact that she remained in San Francisco after the crime – on the premise that she was still in love with Scottie – only served to eventually implicate her in the fraudulent act. This is well captured in one of the film’s final and most memorable lines as delivered by Scottie – ‘You shouldn’t keep souvenirs of a killing. You shouldn’t have been that sentimental.’ Aficionados of the film (myself included) will be only too aware of the extent to which Vertigo has been reappraised in recent years and the simultaneous rise of its reputation. The film is now generally hailed as one of Hitchcock’s very best and there are many of us who regard it as the director’s masterpiece. A pivotal moment for such contemporary praise came by way of Sight and Sound’s 2012 poll of the greatest films of all time – Vertigo replaced Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane at number one on this list. Described as ‘Hitchcock’s supreme and most mysterious piece’, the 45th feature by the master had clearly benefited from its theatrical re-release in the early 1980s and – quite evidently – from its 1996 restoration courtesy of Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz. The lengthy process to return the film to an immaculate condition is outlined in the 1996 documentary Obsessed with Vertigo. Contributors include Martin Scorsese who speaks fondly about his first viewing of the film and how he regards it as Hitchcock’s most personal work.

Fans of Vertigo often refer to their own particular obsession with the film and the way in which it continues to practically mesmerise them with each viewing. Personally speaking, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve watched this atypical psychological thriller, but I’ve little doubt about the lure it continues to hold with respect to its story, themes, production values, performances and, of course, the consummate and singular direction of Hitchcock himself. There are absolutely no compromises in Vertigo and very little in the way of sentimentality or due regard to standard audience expectations. The film simply plays with a distinct lack of concessions and damns its main characters in the process to their private hells and personal tragedies. If anything, the only source of some respite during the 128-minute running time comes by way of Bernard Herrmann’s classic score (his fourth and most telling collaboration with Hitchcock). The American composer’s score is quite simply one of the best ever written for cinema and remains one of the film’s most distinctive and beguiling features. Heartfelt pieces such as Madeleine’s First Appearance, The Flower Shop and By The Fireside contrast sharply with the discordant tones struck in arrangements such as Graveyard and Tombstone, The Forest, The Dream and The Tower; and, of course, the most indelible composition of all is the famous Scene D’Amour which I mentioned previously. Undoubtedly, one of the greatest film scores of all time in my estimation. On this very subject, Martin Scorsese describes how ‘Hitchcock’s film is about obsession, which means that it’s about circling back to the same moment, again and again….and the music is also built around spirals and circles, fulfillment and desire. Herrmann really understood what Hitchcock was going for – he wanted to penetrate to the heart of obsession.’ The obsession with this cinematic tour de force persists 60 years later and shows no sign of abating for us devotees. Quite simply one of the greatest movies ever made. And Hitchcock the filmmaker at the very summit of his remarkable career.