An Evening With Werner Herzog

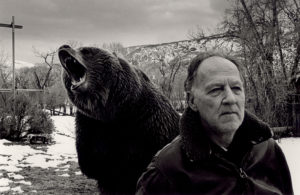

Legendary German film director, screenwriter, author, actor and opera director Werner Herzog partook in a public interview at the 2017 International Literature Festival Dublin in the National Concert Hall and I was privileged to be among those in attendance. The great man, who turns 75 later on this year, spoke about some of the literary passions of his life, as well as his background generally, screenwriting, nature and the thematic forces which often inform his work. He was also more than happy to take questions from the audience with respect to his cinematic endeavours. The interview opened with a recital of a poem Herzog penned himself; titled Rain in the Face, this was written about his grandfather Rudolph. Candid, as always, the director of films such as Aguirre, the Wrath of God, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Fitzcarraldo freely admitted that he had a much closer relationship with his grandfather than his father. Born Werner Stipetic in Munich on the 5th September, 1942, the young boy was all too aware of the harshness of life in the wake of Germany’s defeat in the Second World War. His father Dietrich Herzog was an absent figure during his formative years, and Werner only took the surname (which, incidentally, means Duke in German) because he believed it would sound more impressive for a rising filmmaker.

Asked by the interviewer of the evening if he was a happy schoolboy, Herzog replied no; adding bluntly that he hated it with a ‘profound hatred’ and had serious designs on burning his school down to the ground at one point in time. This was met by some amusement from his captive audience, but he was absolutely in earnest regarding the matter. The famous American film critic Roger Ebert once said of him that Herzog, ‘has never created a single film that is compromised, shameful, made for pragmatic reasons, or uninteresting.’ Whatever the great man says, you can be sure he means. It was a nice light moment – as so many on the evening – but, personally, I have no doubt that he once conceived of such an idea. He also touched upon the matter of being told to sing in front of his class at school and related how he held out on this for as long as possible. He was almost expelled and years later expressed his regret at not having applied himself better and never having studied a musical instrument.

One of the most prominent figures of the New German Cinema, which emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s (along with the likes of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Volker Schlondorff and Wim Wenders), it’s hard now to believe that Herzog had very little exposure to the art form as a young boy. There are no Scorsese or Spielberg-like stories of clandestine visits to the cinema or the local theatre. He fondly remembered the German-French film critic Lotte Eisner who served as his mentor. The director dedicated his 1974 film The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser to her; Wim Wenders paid similar such tribute with his 1984 Palme d’Or-winning film Paris, Texas. Herzog spoke during the interview of how Eisner – a middle-class Jew – was forced to flee Germany when Hitler came to power in the 1930s. He also relayed the personal story of how he set out on foot to visit her when she was critically ill in the mid-1970s. Eisner passed away in 1983.

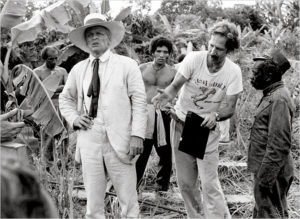

Returning to the subject of literature and language generally, the director referred to the Oxford English Dictionary (‘inexhaustible’ in his words) as the book he would have above all others if he were ever stranded on a desert island. He spoke of his fascination with words such as ‘runt’ and acknowledged that he is fluent in several languages. He read a passage from his own book Conquest of the Useless which he wrote whilst making the troubled Fitzcarraldo in South America. He described this work as being inspired by ‘fever dreams’ he had in the jungle. The problems which cursed principal photography of that film were represented in the 1982 documentary Burden of Dreams by Les Blank. Indeed that very phrase – ‘burden of dreams’ – featured in the text read aloud by Herzog. He referred to the writing of the book as his ‘last resort’ on account of the extraordinary pressures that came to bear in the jungle, by way of on-set disasters, and the regular tantrums thrown by leading man Klaus Kinski.

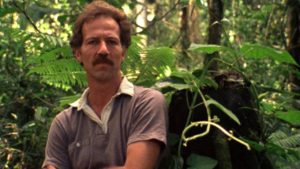

Herzog and Kinski made five films together in total beginning with 1972’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God and ending with 1987’s Cobra Verde. In between these were Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Woyzeck (1979) and the aforementioned Fitzcarraldo (1982). The 1999 documentary My Best Fiend (written and directed by Herzog) concerns their tumultuous personal and professional relationship. The director – also narrating here – recounts how the actor and he lived in close quarters in an apartment in Munich in the mid-1950s. Kinski, a struggling performer, was given to volatile rages and acts of wanton destruction. At the beginning of the film, Herzog visits the apartment in the present-day and reflects upon this, noting how he could not have foreseen then that they would make five films together in subsequent years. But he alludes to Kinski’s great and instinctive skills as an actor when referencing a West German anti-war film titled Children, Mothers and a General. The relationship between the two was especially strained as Fitzcarraldo taxed them both in their respective roles of actor and director. In the documentary Kinski is seen rounding on the unfortunate Fitzcarraldo production manager Walter Saxer for the simple reason that the food is not to his liking. In a typically serene voice-over, Herzog explains how such outbursts served to strain relations with the Indian extras who resolve such conflicts in a very different way. Towards the end of the shoot, one of the chiefs actually approached the director and offered to have Kinski killed. ‘No, for God sake!’ Herzog replied. ‘I still need him for shooting!’ Small wonder so that he describes himself and the deceased actor as being like, ‘two critical masses which result in a dangerous mixture when they come into contact.’

There was another moment from My Best Fiend and Burden of Dreams which I was reminded of as the director spoke briefly about nature and what he termed as its ultimate ‘indifference’ to man. Such a theme is one which has informed feature films of his such as Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo and 2006’s Rescue Dawn; documentary features which readily spring to mind in this latter regard include his Fata Morgana (1971), Grizzly Man (2005), Encounters at the End of the World (2007) and Into the Inferno (2016). Herzog spoke about the stifling nature of the jungle in which death is lurking like an omniscient presence; he vocally disagreed with Kinski’s assessment that the jungle is, ‘full of erotic elements’, but nonetheless professed his own uncommon love of it. ‘But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgement.’

The Peregrine by English author J.A. Baker was mentioned in particular by him as a text which is high on his list as the very best; he has referred to it as ‘the one book I would ask you to read if you want to make films.’ With regard to his Oscar-nominated documentary feature Encounters at the End of the World, Herzog spoke of how he approached the shoot in Antarctica with Virgil’s The Georgics very much in mind. He made reference to Joseph Conrad and Ernest Hemingway, but, in both cases, expressed a preference for their short stories. In Hemingway’s case, the 1936 short story The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber was singled out especially. The director also emphasised his partiality for literary work which comes about through life experience. ‘If you read, you earn the world,’ he advised the audience in the National Concert Hall and it was quite evident that he has an absolute abhorrence of modern-day technologies and practices such as texting which continue to diminish the importance of the written word. In 2013 he released a short documentary titled From One Second to the Next on the theme of the dangers of texting whilst driving. I think there’s little doubt about his sentiments on this particular subject.

When asked by an audience member as to what would be the best piece of advice he could impart on screenwriting, Herzog replied that there was no advice for this specifically, in the same way as there is no advice for writing a poem or a novel. He did refer to the fact that he often writes screenplays very quickly and is well known for encouraging improvisation on his sets. His 1977 film Stroszek, for example, was written in a mere four days and made good use of several biographical details pertaining to its leading man Bruno Schleinstein (credited as Bruno S. in this film and the earlier The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser). Herzog also made it very clear that he has little time for so-called gurus of screenwriting who extol the virtues of three-act structures, internal rhythms and thematic pay-offs. This, and a general disdain for narrow-focused academia, informed his decision to set up his Rogue Film School in 2009. Herzog advises his students to, ‘live life in its elementary form. The Mexicans have a very nice word for it: pura vida. It doesn’t mean just purity of life, but the raw, stark-naked quality of life. And that’s what makes young people more into a filmmaker than academia.’ Most definitely not from any text book on the subject of film studies.

Asked how he rated David Lynch as a filmmaker, Herzog had nothing but praise for his fellow director, but he tempered this with a regret that the Montana-born man has not been very prolific, most especially in recent years. The director fondly remembered shooting part of his 1976 feature film Heart of Glass (in which the majority of his cast performed under hypnosis) on Skellig Michael and spoke of his intention to revisit the island during his stay in Ireland; the Star Wars cast and crew had better make way if they are still filming there. Asked about working with Nicole Kidman on his 2015 film Queen of the Desert (in which she played English writer and explorer Gertrude Bell), the director was laudatory with respect to the Australian actress. When quizzed about being perceived as a director of the male heroic figure (those with impossible dreams such as Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo), Herzog pointed to the central figure of Fini Straubinger from his 1971 documentary film Land of Silence and Darkness. I only saw this film quite recently, but was intensely moved by the story of a deaf-blind German woman who sought out other people like herself in order to discuss and share their struggle. The unimaginable (for us) sense of loneliness and isolation is explored in this wonderful film and Fini was indeed the hero of the piece (‘We share a common fate’). Definitely recommended as one of Herzog’s very best and most thought-provoking documentary features.

Towards the end of the near-two-hour public interview, a member of the audience asked the director which one of his own films was his personal favourite. With a good-natured, yet telling smile on his face, Herzog replied that he loves all his films equally and believes that, in his words, ‘they cannot be improved.’ As an admirer of his films – ever since I first saw The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser in university in the 1990s – I would have to say that my own favourites of his include Kaspar Hauser, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Stroszek, Fitzcarraldo and Rescue Dawn. Fiction short films of his I would recommend are 1968’s Last Words and 1969’s Precautions Against Fanatics. I can’t claim to have seen nearly enough of his documentary feature films (which number some 29 to date by my count), but among these I have a preference for 1971’s Land of Silence and Darkness, 1976’s How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck, 1999’s My Best Fiend (as referred to earlier), 2005’s Grizzly Man and 2007’s Encounters at the End of the World. I hope the great director won’t mind me compiling a Best Of list such as this; I recently purchased the excellent Werner Herzog Collection on Blu Ray which is available through BFI, so hope to catch some more of his documentaries such as God’s Angry Man and The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner in due course. I have a funny feeling indeed that this Best Of list will expand considerably.

Lastly, I should mention how the great man signed off in style at the end of this public interview. Contemplating where he might choose to live if he were ever in a state of exile from his home country, Herzog said that he would probably not live in Siberia, where his wife Lena is from, or America for that matter because of many ‘disquieting’ things which are happening there. The capacity crowd in the National Concert Hall rose to him in an ovation when he finished by saying that Ireland might possibly be his first-choice if he ever had to pick another country to reside in. A piece of showmanship at the finale you might well argue, but it did not have a hollow ring to it either in keeping with everything else he had to say. Werner Herzog will celebrate his 75th birthday on the 5th September, 2017. Here’s hoping he lives another 75 years and makes many more films. Referencing the plot of his own Fitzcarraldo, the great director once said that, ‘Every man should pull a boat over a mountain once in his life.’ He has done this several times in his lifetime and cinema is so much the better for his artistic triumphs.

Great account Kieran, this was sold out before I even knew about it. His films are amazing. Don’t think he’ll be moving here from LA anytime soon though!

Thanks Elaine – it was great indeed to see and hear a living legend up close and personal like that. I agree that I don’t think he will be moving to Ireland anytime soon, but it was evident he was going to be spending a week or two here, particularly in the West.

Maybe he’s checking that Skellig Mhichil wasn’t harmed by those intergalactic space pirates – he got there first!!

He did indeed – for Heart of Glass. I’m looking forward to watching Fitzcarraldo soon again and will be posting a blog on that just as I’ve done with The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek.