In Search of Shangri-La – 80 Years of Lost Horizon

Frank Capra’s seminal fantasy film Lost Horizon, based on the 1933 novel of the same name by author James Hilton, went on general release some 80 years ago in September 1937. The original release date for this Capra classic was the 2nd March, 1937, but any chronicle concerning this film will relate a troubled production which delayed both its distribution and had implications for the version which was first presented to cinema-goers. The Italian-American director was at the very height of his considerable powers throughout the 1930s and this goes some way towards explaining the sizeable budget and artistic licence he was allowed. Films from this period such as 1933’s Lady for a Day and 1934’s Broadway Bill cemented a reputation for mixing overt comedy with sentimental storytelling. 1934’s It Happened One Night, starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, became the first film (and only the third to date) to win the Big Five at the Academy Awards. 1936’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town also garnered rave reviews and earned Capra a second Oscar for Best Director. The New York Film Critics and the National Board of Review both named Deeds the best film of that particular year. The director’s standing within the industry generally and his relationship with Columbia Pictures were in fine fettle. It came as no great surprise, therefore, when the studio’s head Harry Cohn backed Capra in his desire to bring Hilton’s novel to the big screen. Introducing the fictional place named Shangri-La, the novel relates the story of a British diplomat who finds peace and a sense of destiny in this idyllic valley which appears to be sheltered from the vices and attendant pressures of the modern-day world. Shangri-La gradually becomes another word for Utopia – a paradise which is more than imagined, a heaven on earth in which its inhabitants enjoy tranquility and extreme longevity.

English actor Ronald Colman was Capra’s first and only choice for the part of Robert Conway (changed from Hugh Conway in Hilton’s novel) and the director made Mr. Deeds Goes to Town as he awaited the star’s availability. Others cast in the impending production included notables such as Thomas Mitchell (Stagecoach, Gone with the Wind, It’s a Wonderful Life, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), Edward Everett Horton (Top Hat, Here Comes Mr. Jordan), Jane Wyatt (Boomerang, Gentleman’s Agreement) and H.B Warner (It’s a Wonderful Life). The remarkable Sam Jaffe (The Asphalt Jungle, Ben-Hur) was cast as the High Lama after the first two men picked to play this role passed away prior to production. Frequent Capra collaborator Robert Riskin (Lady for a Day, Broadway Bill, It Happened One Night, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town) was hired to adapt the Hilton source material for the silver screen.

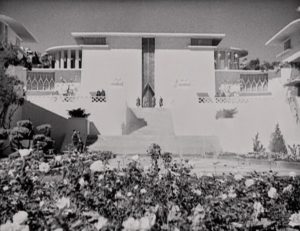

To say that Lost Horizon was an ambitious production is most definitely an understatement. The budget of $1.25 million which Cohn authorised was the largest amount allowed for a project up to that time. The sets by Stephen Goosson – which earned the latter a deserved Oscar for Best Art Direction – are both impressive and elaborate even by today’s standards. During principal photography Capra employed multiple cameras to capture every scene. The net result of such coverage and meticulous attention to detail was a production which far exceeded its original budget and schedule. Filming took approximately one hundred days in total. By the time it wrapped in July 1936, Lost Horizon’s production cost had bloated to $1.6 million; the final cost, including prints and advertising, exceeded $2.5 million. By today’s standards, that seems like peanuts, barely covering as it might the salary of a supporting player, but let’s remind ourselves that this was the 1930s, pre-WWII. When all was said and done, it appeared that Capra was a director who had lost the run of himself. An incredible 1.1 million feet of film had been expended. The first cut of the film ran to an impractical six hours. Even though he managed to trim this down to three-and-a-half hours, the initial preview in Santa Barbara was an unmitigated disaster. Devastated by mostly negative reaction, Capra attempted to make further cuts and re-shot scenes intended to add a more contemporaneous element to the story. Concerned about the film’s commercial prospects, Columbia Pictures weighed in with its own edits and alterations. When first premiered in San Francisco in March 1937, Lost Horizon’s running time came to 132 minutes in total. Eventually, when it went on general release in September of that same year, a further 14 minutes had been removed from the film.

The version of the film which is currently available on DVD and blu ray contains a lengthy titled prologue which goes some way towards explaining the troubled background. The film, which was re-released in 1942 as The Lost Horizon of Shangri-La, had additional footage excised over the years. In 1952, for example, a 92-minute version was released which, purportedly, attempted to downplay certain features of this Utopian vision which were a little too redolent (for some at least) of Communist ideals. One can only speculate with a sense of horror as to what this version was like. Orson Welles had a similar experience with his 1942 period drama The Magnificent Ambersons. Some TV edits of feature films stray into this lamentable area even to this day. Cut too much from a feature story and soon it begins to make no sense whatsoever; it loses its meaning and substance; effectively, it is devoid of its heart and soul. Happily in 1973 (the same year incidentally as the release of a musical remake), the American Film Institute began the process of restoration as it trawled film archives around the world in an effort to locate the lost footage of Lost Horizon. A complete 132-minute soundtrack of the original film was eventually compiled, but, sadly, to this very day some seven minutes of matching film footage are still unaccounted for. The print the viewer can now watch has these missing scenes filled in with freeze frame images and still photos. It’s not the most satisfying of effects, but it’s certainly better than nothing. The search for the absent moments of Lost Horizon continues and one hopes that some fine day these will come to light. In the meantime, we have a classic film which, although incomplete, more than repays repeated viewings. Writing about it at the time of its release, Frank S. Nugent of The New York Times hailed it as, ‘a grand adventure film, magnificently staged, beautifully photographed, and capitally played.’ The Hollywood Reporter called it ‘an artistic tour de force.’ In more contemporary times, the film enjoys a rare 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

One such review refers to it as, ‘one of the most cherished fables made during the Depression era,’ and this indeed is a good way to approach the film if you are a first-timer. Beginning on the 10th March, 1935, the film introduces us to the character of Robert Conway (Colman) – England’s ‘Man of the East’ as he is popularly known. Tasked with the mission of evacuating some ninety westerners from the war-torn city of Baskul in China, the diplomat finds himself on board a plane with his brother George and three perfect strangers. Unbeknownst to them all, their pilot has been overpowered in the cockpit and a new flight course mapped out for them. The central target of this plot or arrangement is Conway himself who is predicted to be England’s next Foreign Secretary. A cruiser in Shanghai is waiting to transport him home. A glittering career seems to beckon and yet Conway is heard to voice his own reservations about this whilst on board the plane – ‘I’ll be the good little boy everybody wants me to be.’ Conway bemoans the fact that he will inevitably fall into line and do the things a Foreign Secretary is expected to do. It’s tempting to view such remarks – as articulated in the screenplay by Riskin – and place them in the context of the world situation as then pertained in the mid-1930s. The Great Depression was rife in America and, overseas, certain pernicious forces were on the rise, particularly in western Europe. The diplomacy of the day would indeed have advocated a moderate and tolerating approach to such threats. The politics of consensus reached its zenith perhaps when in September 1938 British prime minister Neville Chamberlain returned from Munich bearing a piece of paper and an ultimately worthless promise. If Riskin is reflecting on such matters, then he was clearly a writer in tune with his time. The pertinent point for the story in all of this is that, much as he is willing to take up such a position, Conway has his personal doubts as to the effectiveness of such a role. Can one individual make any meaningful changes when the body politic decrees the general thrust of policies and affairs? Will he be merely a puppet who complies with the whims and wishes of his superiors?

Circumstances overtake such thoughts as the group soon come to realise that they are not bound for their supposed destination; a pistol-bearing Chinese pilot is further evidence that something is greatly amiss. After an undefined period of time (and one refuelling stop at a remote village), the plane bearing the five passengers crash-lands deep in the heart of the Himalayan Mountains. Discovering that the pilot has died on impact, Robert and George also find a map on his person. The lost diplomat deduces that they are in ‘unexplored country’; ‘a blank on the map’ as he puts it. The sense of hopelessness and isolation which pervades the group (with the exception of the terminally-ill Gloria Stone (Isabel Jewell) – ‘What a kick I’m going to get watching you squirm for a change!’) is short-lived as a rescue party led by a man named Chang (H.B. Warner) appears on the snow-laden landscape. Much to the delight of Conway and his group, they offer safe passage to their nearby settlement. Upon reaching this, Conway and the others notice how the inhospitable environment of the mountains gives way to a paradise-like setting. ‘Welcome to Shangri-La,’ Chang whispers to the diplomat. The environment is blissful and the attendant remoteness is further underlined as Chang subsequently advises that there are no means of communication with the outside world. The land and people sustain themselves; food is never in short supply; porters rarely traverse the area; there are no soldiers or police on account of the fact that there is no crime. Professing as he does an instant fondness for Shangri-La, Conway is unable to shake the notion that he has been in this place before. The historical background is provided by Chang who tells the story of a Belgian priest named Father Perrault who founded Shangri-La. Crediting an ‘absence of struggle’, Chang also reveals how individuals in the area live for a remarkably long period of time. Because there is no lack of anything, there are no consequent desires of need, want or greed. Even conflicts of love and sexual longing are settled in a peaceful manner. Good manners dictate that one man steps aside for another man in this regard. Conway is particularly glad to hear this as he takes a definite shine to a young woman named Sondra (Jane Wyatt).

The other passengers Alexander P. Lovett (Edward Everett Horton) and Henry Barnard (Thomas Mitchell) begin to warm to their new surroundings, as Conway himself does (the sick Gloria recovers from her seemingly incurable illness), but George resists the lure of Shangri-La and continues to demand answers and safe passage. When Robert enquires as to why the group are being kept here (admittedly in very hospitable conditions), Chang informs him that the High Lama (Sam Jaffe) wishes to see him. In this first meeting, the High Lama sets out his vision for Shangri-La’s future as well as that of Conway – ‘We need men like you here,’ he tells the Englishman, who has realised that the High Lama is in fact the aforementioned Father Perrault. The centuries-old cleric voices his aspiration that Shangri-La will become a beacon of hope for the rest of the world; a simple maxim is articulated in this respect – ‘Be kind.’ Elsewhere, the Sermon on the Mount is referenced – ‘And the meek shall inherit the earth.’

In spite of Conway’s confusion on the point, the message being conveyed to him here is that he is the chosen successor to the High Lama. This is further reinforced as he speaks to Sondra some time following this pivotal meeting. ‘I saw a man whose life was empty,’ she tells him as she explains that she was the one who suggested his coming. ‘Perhaps you’ve always been a part of Shangri-La without knowing it,’ she suggests as he expresses once again a persisting feeling that he has been here before. When Conway enquires as to whether she ever wanted to return to the outside world, the response he receives is a definite no. When George threatens to attempt to leave Shangri-La, Robert confers with the High Lama on this matter. This second and final meeting is even more significant than the first as the much older man effectively bequeaths the spiritual leadership of Shangri-La to Conway – ‘I knew my work was done when I first set eyes upon you,’ he tells Robert, ‘you will preserve the fragrance of our history.’ The High Lama passes away with these words and a ceremony is subsequently held to mark his death. The passing of the torch appears to be a foregone conclusion until George sows the seeds of doubt in Robert’s mind. Convincing his older brother that Shangri-La is not quite what it is made out to be, George also insists that the little Russian girl Maria, whom he has befriended, is not actually an old woman who has been living there since 1888 according to Chang. ‘We’re living in the 20th Century!’ he exclaims as he urges Robert to leave with them. The long-awaited porters have arrived and can escort them back to civilisation; Robert might yet become Foreign Secretary upon his return to England. Maria too weighs in with her own opinion when she describes the High Lama as ‘insane.’

His abiding reservations suitably raised, Robert decides to accompany them. Duty and sacrifice in the public realm remain principles he can still adhere to. Perhaps the life mapped out for him by the High Lama and Sondra seems too effortless and carefree. Perhaps he doubts the grandeur of the dream presented by Shangri-La. The ensuing journey on the outside does not go well. The porters prove to be treacherous as they mock the three, taking pot shots at them on a regular basis. One such wayward incident leads to an avalanche which engulfs them. As they travel on alone, Robert and George soon discover that Chang had been telling the truth about Maria; she suddenly ages and dies. A despairing George throws himself to his death. Realising his grievous error, Robert attempts to return to Shangri-La, but fails in the unforgiving conditions. Found alive by locals, news of his rescue becomes the subject of headlines the world over and it is reported that he has suffered a total loss of memory. A fellow diplomat, Lord Gainsford, is dispatched to convey him home; however, Gainsford returns to London without Conway. In a social club towards the end of the film, Gainsford relates the story of how Robert eventually regained his memory and spoke of nothing else but Shangri-La. An obsession eventually overpowering him – in Gainsford’s words – Robert escaped with the singular intention of getting back to that Utopian world. As his peer raises a toast to him (‘Here’s my hope that Robert Conway will find his Shangri-La. Here’s my hope that we all find our Shangri-La’), the film concludes with a memorable image of Conway as he re-enters his beloved paradise. His choice determined and final on this occasion, the diplomat can undoubtedly look forward to a very long and rewarding life. The struggles and vicissitudes of the everyday are now firmly behind him. Peace and harmony await.

This begs the question of course as to what kind of vision of the world Hilton, Riskin and Capra are presenting us with as they relate Conway’s eventual choice, which does seem entirely rational and clear-cut. The 1933 novel itself was written during the first half of the Great Depression and the screenplay by Riskin begun during the latter period which lasted almost to the time of the Second World War. Riskin, who was originally a playwright on Broadway, witnessed the closure of many theatres after 1929 and one can only assume that this and the dip in his personal fortunes informed his decision to relocate to Hollywood in the 1930s. Hilton – who also penned the equally wonderful Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1934) – was said to have been influenced by the National Geographic articles of Joseph Rock, an Austrian-American explorer, geographer, botanist and linguist, who explored the southwestern Chinese provinces and Tibetan borderlands. The name Shangri-La itself has long since entered the popular vernacular and is – as we know – a byword for a fabled place or an ideal world. It’s impossible to imagine that either Hilton or Riskin carried out their respective work in a creative vacuum, entirely oblivious of events in the greater socio-economic sphere. In Hilton’s case the primary issues of the day would have included poverty, want and human degradation. For Riskin these matters would also have been self-evident, as well as the general spectre of a looming world war. Shangri-La is, therefore, posited as an alternative to such menaces and inherent hardship. The ultimate choice made by Conway is one which represents the personal over the universal, the sentimental over the hard-headed. Perhaps the essential message which is being imparted here is that man and his sophisticated institutions have failed. There is a strong emphasis throughout the story on the simple life, the uncomplicated path. Such a viewpoint is entirely intelligible when one considers the events of the world during this era. It’s surprising, therefore, that Lost Horizon was a commercial failure in its day given its hopeful message. Fortunately, this classic fantasy has more than stood the test of time and remains one of Capra’s greatest works. This fan of the film, for one, hopes that the lost footage, as referenced earlier, will someday be found. Meantime, we earnestly encourage anyone who has not previously seen it to watch Lost Horizon as it celebrates its 80th birthday. Welcome to Shangri-La indeed.