Movie Retrospective: A Matter of Life and Death

Some three-quarters of a century after its first theatrical release, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death remains a glorious oddity. Billed primarily as a fantasy-romance, the 1946 film is said to have been suggested to the writer-directors as a vehicle for soothing somewhat fractious relations between England and America in the aftermath of the Second World War. Released the same year that Winston Churchill coined the phrase ‘the special relationship’, there can be no mistaking the possible intent of the film in such an overarching context. At its heart after all is the story of a Royal Air Force pilot Peter (David Niven) who falls for an American radio operator named June (Kim Hunter). The circumstances of their first meeting are as tenuous as you could imagine. His Lancaster Bomber badly damaged following a raid in Germany, Niven’s character is certain that his number is up. His crew is dead and he has no parachute with which to bail out. The only recourse left open to him is to speak with the pretty voice on the other end of the radio. This so happens to be June. At the end of the short but meaningful conversation, Peter gives his impending fate a gentle nudge. He dives out of the plane and falls to his apparent death – ‘You’re life June, and I’m leaving you.’

The element of fantasy which prevails throughout the film is continued as Peter awakens on a beach the following morning. At first he believes he is in the afterlife, but his eyes and ears soon tell him differently. By sheer coincidence (or perhaps not), he soon meets June who is stationed close by. Falling in love immediately, the two are inseparable, but a higher authority in the guise of a French aristocrat known as Conductor 71 (Marius Goring) has other ideas. As it transpires, the fact of the matter is that Peter should have died from his fall, but was missed owing to the thick fog – ‘Your time was up. But they missed you because of your ridiculous English climate.’ And so begins the central struggle of the film. The heavenly representative is insistent that Peter should accept his destiny and surrender to heaven; the smitten pilot on the other hand argues that his circumstances have now changed entirely on account of his love for June. The matter of life and death of the title is one incorporating the theme of human fortitude and the instinct for survival in the face of a seemingly unrelenting force. I wonder if this is part of the reason why Powell and Pressburger chose to present the scenes in heaven in Technicolor Dye-Monochrome whilst rendering the passages on Earth in Three-Strip Technicolor.

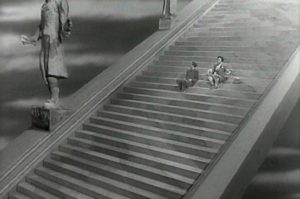

Comparisons to contemporary films of the time abound, in particular Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (also released in 1946). A viewing of this essential classic will confirm such similarities with respect to theme and tone. In the same vein as the Jimmy Stewart vehicle, A Matter of Life and Death returns constantly to the idea that life is precious and should not be taken for granted. On more than one occasion we witness Peter in a philosophical and physical battle for his very existence. Given a temporary reprieve by the celestial powers-that-be, he must successfully argue his case for a life beyond the time of the fatal air raid. It’s interesting to note that in the United States the film was originally released under the title Stairway to Heaven. The principal reason for this was the concern that the mere mention of the word death in the actual title might prove to be a damper and, thereby, impede the film’s chances at the box office. In a curious way the hastily-created title for the American market was not without merit. The most affecting visual of the film is surely the stairway which appears prominently during the scenes set in heaven. At one such moment, the aforementioned Conductor 71 attempts to trick Peter by having him linger on the ascending staircase. The latter – who is now suffering from a supposed brain injury – spots the ruse just in time and returns to consciousness. A key question which the filmmakers confront us with is the matter of what is real and what may be imagined. Are Peter’s ‘visions’ a symptom of his degenerating physical condition or a manifestation of the tussle which is occurring for him as he finds himself pulled between heaven and earth?

As with any classic film, it helps greatly that we are watching several actors at the very top of their game. In the lead role, David Niven has scarcely been better as Peter, the man whose life dangles indeterminately as he seeks to find a defence counsel who can help him win his case. Best known perhaps for his roles in films such as Around the World in Eighty Days, Separate Tables and The Guns of Navarone, Niven is often associated with the image of the quintessential English gentleman, but he drops his guard here to brilliant effect and gains audience empathy in the process. The film-making team that was Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger produced some sterling work in their time (including 1947’s Black Narcissus and 1948’s The Red Shoes), but 1943’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is especially apt for mention here as its leading actor Roger Livesey plays the part of Dr. Frank Reeves, an affable physician who attempts to help Peter and also understand the underlying cause of his ‘visions.’ In the supporting role of June, Kim Hunter is similarly sublime and other notables among the cast include Raymond Massey, the aforementioned Marius Goring, Black Narcissus’s Kathleen Byron and a young Richard Attenborough in just his fifth film. I’ve little doubt that the future director of Gandhi and Shadowlands was duly impressed by the sizable efforts of Powell and Pressburger. In terms of the film’s distinctive look and superlative set design, great credit must also be apportioned to regular Powell and Pressburger collaborators Jack Cardiff (director of photography) and Alfred Junge (production designer).

Matters come to a dramatic head as Peter’s physical condition worsens and he undergoes brain surgery. In tandem with this are the scenes played out in the other world in which the recently-deceased Reeves (killed in a motorcycle accident) acts as Peter’s counsel. Reeves further elaborates on the argument that his client’s new earthly commitment (apropos Peter’s relationship with June) should now take precedence over the afterlife’s claim upon him. In the film’s most knowing reference to the historical context of Anglo-American relations, the prosecutor is the American Abraham Farlan (Massey), a man who has a personal gripe with the English as he was the first casualty of the American War of Independence. Reeves and Farlan go head-to-head as they cite various examples from the history of mankind to substantiate their respective cases. The denouement of the piece arrives as Reeves has June take the stand to prove that she truly loves him. The latter agrees to take Peter’s place on the stairway to the other world, but the film has a satisfactory conclusion as this comes to an abrupt halt and she rushes back to his open arms. The words spoken by Reeves as he offers a reply to the observation of Farlan are a perfect summation for the end of the film – ‘Yes, Mr. Farlan nothing is stronger than the law in the universe, but on Earth nothing is stronger than love.’ Unsurprisingly, the jury rules in Peter’s favour and – on Earth – his surgery is declared to be a success.

Released in the UK in November 1946, and in the United States in December 1946, A Matter of Life and Death’s reputation has deservedly grown in the intervening years and it is now hailed as a classic of its kind. The British Film Institute ranked it 20th in its 1999 poll of the greatest British films of the 20th Century. More recently, in 2012, film critics listed it as the 90th greatest film ever made in the Sight & Sound poll. I previously suggested the innate peculiarity of its subject matter for it does not neatly fit in any specific genre. On the one hand it’s a fantasy-romance when one considers the love story at its heart; on the other, it’s a dramatic piece on the enduring quality of the human spirit, on man’s inherent desire to be wanted, to be loved, to be of purpose. The most unquestionable feature of the film some three-quarters of a century later is the audacity of Powell and Pressburger’s vision. Although presented in monochrome, their portrait of heaven is one replete with stark imagery and fastidious detail. The aforementioned Conductor 71 may well bemoan the fact that ‘One is starved for Technicolor up there’, but this is certainly not the impression one is left with on a repeated viewing. In keeping with the remark by Roger Livesey’s character (as quoted above), I believe the decision on the part of the directors to depict Earth in Three-Strip Technicolor was taken in order to emphasise the vibrancy of life and the pre-eminence of romance over regulation. Some 75 years later, it continues to strike a beautiful chord in this respect and A Matter of Life and Death retains its classic status.