Movie Retrospective: Little Big Man

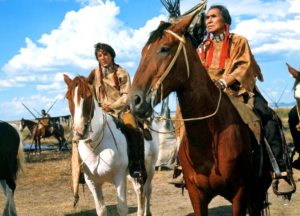

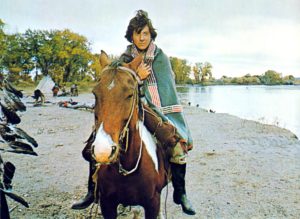

Based on the picaresque 1964 novel of the same name by Thomas Berger, Little Big Man relates the story of one Jack Crabb, a white man who is raised by the Cheyenne tribe as one of their own following the massacre of his parents at the hands of the Pawnee. The 1970 film directed by Arthur Penn (The Left Handed Gun, Bonnie and Clyde), and starring Dustin Hoffman in the title role, has been described as a motion picture which encompasses several genres, including comedy, drama and adventure. Most properly, it can be considered a western – and a revisionist one at that. This is a film which undoubtedly depicts the Native Americans and their way of life in a sympathetic manner. In stark contrast to this is the representation of the United States Cavalry, and. in particular, General George Armstrong Custer (Richard Mulligan). Other prominent cast members include Martin Balsam, Faye Dunaway, Chief Dan George and Jeff Corey, who portrays another famous historical character of the Old West – Wild Bill Hickok.

Little Big Man opens with the 121-year-old Crabb recounting how his family was wiped out by a ‘band of wild Indians.’ Describing himself somewhat portentously as the ‘sole white survivor of the Battle of Little Bighorn’, Crabb proceeds to set an incredulous historian (William Hickey) straight on certain facts concerning Custer and the Native Americans upon whom he waged war. The intention of this short prologue section is to set the historical context and establish that the story we will be hearing about is at some remove in the past. Much commentary in relation to the book, and subsequent screen adaptation, centres on how much of Crabb’s story is true and how much may be fabrication. The notion of the unreliable narrator raises its head in this respect. Commenting on the film at the time of its release, Roger Ebert described it as ‘an endlessly entertaining attempt to spin an epic in the form of a yarn.’

Crabb and his sister Caroline (Carole Androsky) are rescued by a brave called Shadow That Comes in Sight and taken to a Cheyenne village. The character of the benevolent tribal leader Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George) is first introduced at this point and Crabb relates how he came to regard the older man as his grandfather. There are some interesting observations made on the Native American way of life at this early stage. Crabb refers to the Cheyenne as the ‘human begins’; he also tells of how he himself was ‘living Indian’ as he puts it. Watching this film for perhaps the fifth or sixth time now, I was indeed struck by the contrasting views it has as regards pioneer life and the practices and customs of the Indians. Little Big Man has elements of humour and pathos throughout its 139-minute running time, but I would suggest that elegiac is its most predominant and abiding tone. In this latter regard, I would point most especially to the relationship between Crabb’s character and that of Old Lodge Skins. The wise and droll tribal leader is the one who gives Crabb his Indian name – Little Big Man (on account of his short size but intrepid disposition). His decision to wage war on the white man following a massacre is however less grounded in terms of common sense. Armed only with their traditional weapons, the Cheyenne are easily defeated and Jack himself is captured during the skirmish. Captured may very well be a loose term here as – in truth – he appears to give himself up all too readily as he declares himself to be white (‘God bless George Washington!’). He is then turned over to the care of the Reverend Silas Pendrake (‘We shall have to beat the lying out of you’) and his seemingly pious wife Louise (Faye Dunaway).

Again the notion of the unreliable narrator raises its head at this point. Crabb is shown to be self-serving at various points in his life when choices are limited and needs must. His surrender to the white troops – as mentioned above – seems somewhat convenient and informed by an overall desire to survive in this frontier setting which can often be severe and potentially deadly. Staying with the Pendrakes for only a short time, the young Jack appears to embrace religion, but is quickly dissuaded from such a course when he learns that Miss Pendrake is not as pure of mind and body as she makes out to be. Little Big Man is remarkable for the number of white characters who, like Jack himself, do what is expedient to the moment and often succumb to the pleasures of the flesh. The snake-oil salesman Allardyce T. Meriweather (Martin Balsam), with whom Jack next takes up with, is one such illustration of this type. When Meriweather and Jack are tarred and feathered by a group of duped members of the public, we are only slightly surprised to learn that one of these is the latter’s long-lost sister Caroline. Little Big Man has this episodic feel to it and this is one of the many aspects which make it such a rich and memorable piece of work.

Jack’s so-called ‘gunslinger period’ is also the occasion for his first encounter with Wild Bill Hickok (Jeff Corey). The bar scene in which the self-titled Soda Pop Kid shares a drink with the seasoned Hickok is, without doubt, one of the film’s most amusing sequences. When he witnesses Hickok gun down a man, Jack decides to hang up his own holster and a disgusted Caroline quits him. The next chapter involves him marrying a Swedish woman, by the name of Olga, and starting a hardware store with a partner whom we never see onscreen. Jack’s partner is revealed to be a thief and the distraught couple are advised by a self-important George Custer to go west in order to improve their prospects. ‘You have nothing to fear from Indians, I give you my guarantee,’ he tells Olga, but the very next scene proves the General to be entirely erroneous in this piece of advice. Olga is abducted by the Indians and Jack searches for her to no avail. Venturing deep into Cheyenne country, he is reunited with Old Lodge Skins (‘To see you again causes my heart to soar like a hawk’) and two other Indians from his boyhood days – the slightly volatile Younger Bear and the decidedly effeminate Little Horse.

Crabb’s alternating life cycle continues as he temporarily becomes a muleskinner in the employ of Custer’s forces, and then returns to the Cheyenne camp taking up with the daughter of Shadow That Comes in Sight. Again, the narrator and – by extension – the filmmakers leave us in little doubt as to their views on the marauding regiments of the United States Cavalry. The enmity the central character feels towards Custer and his underlings takes on a distinctively personal tone when he learns that Old Lodge Skins has been blinded in combat (‘Do you hate them? Do you hate the white man now?’). This becomes even more intense with the Battle of Washita River which is Little Big Man’s most pivotal and harrowing scene. Sunshine (Jack’s second wife) is shot dead in the most merciless fashion and Crabb vows vengeance on Custer. Rejoining the egotistical General’s camp, Jack determines to assassinate him, but does not go through with his plot. Despondent and defeated, he becomes a drunk for a period of time before again meeting with Wild Bill Hickok. The folk hero gives him some money which he instructs must be passed on to a high-class prostitute. Hickok is shot dead and Jack visits her only to learn that it is Miss Pendrake under the name of Lulu. Becoming a hermit subsequently, Jack decides to end his own life, but is persuaded otherwise when he hears the march of Custer’s Cavalry regiment in the distance. ‘The time had come to look the devil in the eye and send him where he belonged’ he tells us as he once again presents himself to Custer. Spurred on by his never-relenting self-conceit, the General decides that Crabb will serve as the ‘perfect reverse barometer’ as anything he says will be a lie and the opposite of what he should do.

Crabb’s life is saved at the ensuing Battle of Little Bighorn by Younger Bear who tersely informs him that now that he has returned his debt, he can kill him the next time they meet without becoming an evil person. The film ends in an elegiac fashion (the predominant tone which I referred to earlier) as Jack accompanies Old Lodge Skins to a nearby hill – an Indian burial ground – where the old man is convinced he will shortly pass (‘It is a good day to die’). The undercurrent of humour which also abounds throughout the film returns as a rainstorm puts paid to the old man’s wishes – ‘Sometimes the magic works, sometimes it doesn’t.’ The book-ending device is complete as the elderly Crabb dismisses the historian with the words ‘Get out! Get out!’ As he places his hand on his weathered brow, the implication clearly is that he is bemoaning a life he once knew which has long since passed into history. The mournful final piece of music by composer John Hammond serves to corroborate as much. Whatever the exact truth of Crabb’s story (we have only heard his version of things after all), the old man laments an existence that is no longer current and no longer tenable. Modern civilisation has long since ousted the ‘human beings’ from their rightful lands. The incessant force of progress has prevailed. To no small extent, Custer has, in fact, won the day.

Directed with a suitably epic, yet tragic-comic tone by Arthur Penn, this superb 1970 film boasts an excellent supporting cast which includes the aforementioned Balsam, Dunaway, Jeff Corey and Richard Mulligan. Hoffman is in characteristically superlative form as the titular character, but the scene-stealing performance here undoubtedly belongs to Chief Dan George (who also featured to winning effect in Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales) who received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination as Old Lodge Skins. For his scenes as the 121-year-old Crabb, Hoffman apparently screamed at the top of his lungs for an hour in order to effect the gravelly sound of his effect. As well as Penn and the cast, kudos also to director of photography Harry Stradling Jr. and screenwriter Calder Willigham. A blu ray copy of the film is now available and quite beautiful to look at. One of the best American films of the early 1970s.