Movie Retrospective: The Naked City

The streets of New York City during a long hot post-war Summer is the main setting for Jules Dassin’s memorable police procedural The Naked City. Filmed in 1947 and released in March 1948, The Naked City begins with an off-screen narration by the film’s own producer Mark Hellinger as Dassin and his cinematographer William H. Daniels pick out some commonplace images from the city that never sleeps. ‘This is a story about the city itself,’ Hellinger tells us in a worldly-wise way as he emphasises the real-life locations which are presented to us. The daytime scenes have a distinctly docudrama style to them in keeping with one of the film’s most fundamental premises. At night-time, however, Dassin switches to the central core of the story – a murder in an apartment is in progress. A young woman is, ‘at the end of her life,’ in Hellinger’s words. The following morning we watch as one of the perpetrators turns on the other and coldly tosses him into the East River. The victim of their crime is revealed to be one Jean Dexter – a once aspiring model. The grim discovery of her lifeless body is made by a house worker. Jean – as it turns out – was rendered unconscious with chloroform and then drowned in her own bathtub. The chief investigator assigned to the homicide is the veteran Detective-Lieutenant Dan Muldoon (as played by Barry Fitzgerald).

‘Looks to me like a heavy case,’ he observes as the preliminary facts of the crime come to light. The dead woman’s jewellery is missing and there is mention of an older admirer by the name of Mr. Henderson. A prescription for pills is also unearthed and Muldoon’s underling, Detective Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor), follows up on the lead. He is informed by a Dr. Lawrence Stoneman that the deceased took stimulants by day and sleeping pills by night. Dexter, evidently, was a young woman who wished to get ahead in a hurry. But she paid a heavy price for such unbridled ambition. When her estranged parents arrive in the city to identify their daughter, Jean’s mother reflects on advice which went unheeded – ‘I told her. I knew she’d turn out no good. All these young girls. So crazy to be with the bright lights. No bright lights for her now.’ One of The Naked City’s most indelible qualities is its employment of some of the most familiar landmarks of New York during the course of the film. With a darkening Brooklyn Bridge serving as a backdrop, Jean’s mother regrets her good looks and desire to get ahead in this alluring but perilous world – ‘Dear God! Why wasn’t she born ugly?’ The story by Malvin Wald has as its focal point a protagonist we never actually get to meet – Jean Dexter’s story is a fantasy tale gone horribly wrong; her involvement with certain undesirable elements has led to her light being put out for all time. Alice has not prospered in this particular wonderland. The hole she has descended into has eventually proven too deep.

But Dexter was far from being some sort of ingenue who knew no better. Questioning a highly dubious character by the name of Frank Niles (Howard Duff), Muldoon establishes that the two were intimately involved. A compulsive liar by nature, Niles invents stories about his so-called service during the Second World War and also about his thriving business. ‘I’m only a small-time liar,’ he maintains as he pleads innocent to Jean’s death, which is true as it turns out he has a credible alibi. The seasoned Muldoon suspects, however, that he knows more than he is letting on; such proves to be the case when Niles also attempts to mislead Muldoon as regards his association with Ruth Morrison (Dorothy Hart), a former colleague and friend of Dexter’s.

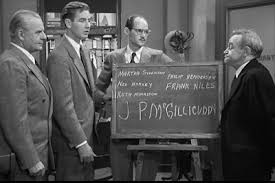

The introduction of Muldoon’s fictional unknown character in a murder case – J.P. McGillicuddy – is a clear acknowledgement by the screenwriters Malvin Wald and Albert Maltz that we are firmly in the realms of the police procedural genre here. The investigation – which exposes further thefts of jewelley and precious possessions – is in keeping with such a style and form, but the first-time viewer should also marvel at the way in which Dassin merges elements of film noir and mystery-suspense. When the body of the second murderer is discovered by a group of boys in the river, there is an ominous sense that this occurrence happens all too often in this city of millions. Hellinger’s omniscient narrative suggests as much too in the way he functionally, almost coldly, sets out the course of the investigation. The character of Frank Niles is the embodiment of the unpleasant substratum which Dassin and his writers are eager to draw our attention to. Little more than a petty thief and a grifter, Niles will do just about anything to protect himself from both the forces of law and disorder. The engagement ring which he has presented to his fiancee Morrison is a stolen piece and even an attempt on his own life sees him as an unwilling informant. But the persistent Muldoon and Halloran learn that he and Dexter were accomplices who targeted properties which they knew were ripe for the taking. The aforementioned Mr. Henderson turns out to be none other than Dr. Stoneman whom Halloran had previously interviewed. Adamant that he did not kill the murder victim, he informs the police of how Dexter and Niles had used his social connections to carry out their burglaries. The two then employed other men for such work and one of these included a former wrestler/acrobat by the name of Willie Garzah.

The Oscar-winning Barry Fitzgerald receives top billing here, but, in truth, the real star of The Naked City is New York itself. The film benefits greatly from the method employed by Dassin to present to us a living, breathing metropolis in which any number of narratives are playing out at the same time and, sometimes, in opposition to one another. These are the ‘eight million stories’ which Hellinger’s narrative refers to at the film’s conclusion which involves the Williamsburg Bridge. Responsible for both the deaths of Jean Dexter and his co-conspirator, Garzah’s pursuit is the fitting climactic scene which The Naked City so richly deserves. In spite of his assertion that, ‘this is a great big, beautiful city,’ Garzah soon comes to realise how ineffective his attempts at elusion are when married with a guilty disposition. There’s a gloriously memorable shot as actor Ted de Corsia (Garzah) stares down from the top of the suspension bridge and views the city for one last time. His own story is close to an end and by tomorrow few will remember his name or face. Dassin indicates as much as we see a paper bearing the headline ‘Dexter Murder Solved’ being swept up from the sidewalk. Jean Dexter’s name is now also becoming a thing of the past. The living city has little use for the dead and departed. It sustains itself with its future and those remaining eight million souls who contribute to its pulse and its vitality.

Winner of two Academy Awards – for cinematography and film editing – The Naked City has cemented its reputation as one of the very finest in this particular genre and it also benefits from the performances of the likes of Barry Fitzgerald and Don Taylor. The visual style – which is so dominated by the iconic city itself – was inspired by a photographer by the name of Arthur Fellig (better known perhaps by his pseudonym Weegee) who was famous for his stark black-and-white street photography. Naked City (1945) was the latter’s first book of photographs, the rights to which were purchased by producer Mark Hellinger. Weegee was hired as a visual consultant on the film and subsequently went on to work on other productions such as Kubrick’s 1964 Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove. A television show of the same name was broadcast from 1958 to 1959 and then again between 1960 and 1963. Utilising the same dramatic semi-documentary format, the popular series also concluded with the film’s celebrated closing line – ‘There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them.’ This 1948 classic is also one of the very best of them. Unsentimental, hard-hitting and beautifully gritty through and through.