Movie Review: Filmworker

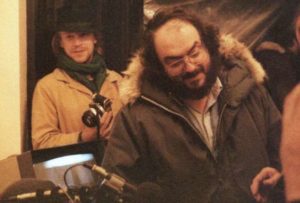

The question at the core of Tony Zierra’s documentary Filmworker is as follows, and it’s one which the film returns to repeatedly during its 95-minute running time: Why would a young actor whose career was on the rise decide to sacrifice his own ambitions and talents in the service of a brilliant but notoriously difficult director? Leon Vitali – the central character of the piece – was an emerging actor in his mid-twenties when he was cast in the role of Lord Bullingdon in Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film Barry Lyndon, an adaptation of the novel by William Makepeace Thackeray. At an early point in the documentary, Vitali describes his first viewing of Kubrick’s groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey. The enthusiasm and devotion for the master and his work is highly infectious and effusive. It helps a great deal if you are a Kubrick fan, as this reviewer is. But if you watch Filmworker without some level of understanding of Kubrick’s work and his legacy to cinema, then Filmworker is a far less effective piece. The artistic quality of the director, who passed away in 1999, is far less palpable. And the unrelenting loyalty of Vitali himself is rendered much more oblique as a result.

Filmworker is, therefore, a film for Kubrick enthusiasts first and foremost. The personal journey for Vitali himself begins with principal photography of Barry Lyndon in the mid-1970s. Vitali is a compelling enough narrator and he relates with good measure his fascination with the film process generally. It helped greatly that he just so happened to be working on one of the most gorgeously shot films in modern-day cinema. The winner of four technical Academy Awards, the period drama remains one of Kubrick’s most astounding achievements in terms of its aesthetic qualities. But there are early hints as to the mania and obsession which underlay the Kubrick process. The film’s star Ryan O’Neal speaks of the sequence in which his character publicly assaults Lord Bullingdon, as played by Vitali. Those of us familiar with the anecdotes will nod our heads as we listen to accounts of multiple takes. But Vitali – to his credit – was not deterred by any of this. When shooting eventually concluded, he let it be known that he wished to continue his association with the director in whatever future ventures took his fancy. The upshot was that he was sent a copy of Stephen King’s 1977 novel The Shining.

Vitali became a factotum to Kubrick on this next film and went on to work on the director’s last two films thereafter, namely 1987’s Full Metal Jacket and 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut. When asked at a later stage of the documentary if he ‘handled Stanley’, Vitali is quite adamant in his response. ‘No’ he says ‘I handled myself so that I could exist in Stanley’s world.’ Although beset by financial difficulties and a typically arduous production generally, The Shining somehow emerges as one of Vitali’s better experiences under Kubrick. The former actor (who by this time had abandoned his career in front of the camera) was responsible for the casting of Danny Lloyd in the pivotal role of Danny Torrance. He also discovered the twins who played the murdered daughters of the former caretaker Charles Grady. But other information has been excised here. There is no mention of the trauma suffered by actress Shelley Duvall during the shoot; nor the pioneering use of the newly-developed Steadicam which was extensively employed during the course of principal photography.

If anything, 1987’s Full Metal Jacket emerges as a much more problematic project. Vitali speaks of the stress Kubrick was under which, in turn, was often passed on to himself. The duties and responsibilities proliferated and, at times, one can’t help but feeling he was treated as a general dogsbody. To this effect we hear of calls made on Christmas Day and instructions to clean rooms and monitor Kubrick’s ailing cat. More rewarding work came as the director looked towards his legacy and entrusted his right hand man with preservation work on his dozen or so feature films. Vitali continued this work after Kubrick’s passing and is clearly at pains to emphasise how much more difficult it became when the director was no longer there to back him up. With respect to Kubrick’s final film Eyes Wide Shut, it effectively fell upon Vitali to deliver the end product when the director died before its theatrical release. One feels the pain more often than the pleasure which arises when attention to detail goes beyond the nth degree. On a personal level Kubrick is described as charming, intelligent and articulate; on the flip side, he is likened to Gordon Ramsay in relation to the verbal invectives he was capable of. Actors who worked with Kubrick – such as Matthew Modine and R. Lee Ermey – marvel at the commitment displayed by Vitali throughout. The subject of the documentary himself reflects that his own story had a happy ending because he worked with and for and continues to work on behalf of one of the masters of modern cinema.

The focus on the work of preserving and enhancing Kubrick’s legacy to cinema takes up much of the final third of the film, but some gaps in the overall story present themselves. We see interviews with Vitali’s children, but learn little about his personal life generally and the effect his work had on his adult relationships. Zierra’s documentary awkwardly transitions back to Vitali’s childhood and attempts to posit a vague connection between the actor’s father (who died when he was 8) and Kubrick himself. It feels forced to suggest that the director became something of a surrogate father, but this appears to be the implication. Of more pertinent import perhaps is the fact that Vitali was treated with mild disdain by the powers-that-be at Warner Brothers as he toiled on the preservation and restoration of several key works; he was also snubbed when an exhibition devoted to Kubrick opened in Los Angeles in 2012. Zierra’s film is a timely and appropriate piece in that context and Vitali (now approaching 70) is due the credit and recognition he deserves. This is a film about unselfish and unwavering allegiance in the cause of cinema and art generally. Its central protagonist emerges as a gracious and humble man who was a constant at the side of a great director during the twilight years of his career. A must for Kubrick fans and an intriguing insight into the world of one of his greatest and most intimate aficionados.

Rating: B