Movie Review: My Cousin Rachel (2017)

Mystery and ambiguity are common hallmarks of the work of British author Daphne du Maurier (Jamaica Inn, Rebecca and short stories such as Monte Verita, The Apple Tree and Don’t Look Now) and they are most certainly ingredients which inform her 1951 novel My Cousin Rachel, now adapted again for the big screen by director Roger Michell (Notting Hill, Venus). Screen adaptations of du Maurier’s work famously include three films by Alfred Hitchcock – Jamaica Inn (1939), Rebecca (1940) and The Birds (1963) – and Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973). What’s quite interesting about these adaptations is that, with the notable exception of The Birds, they were made into films within a relatively short period of time following the original publication of the source material. The first such version of My Cousin Rachel – released as early as 1952 (with Olivia de Havilland in the title role and a very youthful Richard Burton as Philip Ashley) – followed this pattern and one wonders what exactly has prompted this new adaptation some 65 years later. The story will be familiar to many a du Maurier fan with respect to its Cornwall setting and motifs pertaining to shadowy forces and equivocal motivations. Philip Ashley (Sam Claflin) has been an orphan for the greater part of his life, but has enjoyed the sizeable benevolence of his older cousin Ambrose, who is the owner of a large country estate situated on the Cornish coast. Ambrose is not accorded a speaking part here, rather we see him briefly as he sets off for the sunnier climes of Italy in the hope of restoring his declining health. At an early point in his narrative voiceover, Philip notes how women were not a part of Ambrose’s household (the only females who entered the house were, in fact, dogs he categorically states) and Ambrose’s letters regarding their cousin Rachel, whom he has become romantically involved with, take the young man by surprise at first. This emotion soon changes to concern after the two marry and Ambrose hints that his bride may not be quite the paragon of virtue he once supposed. In particular, he details his recurring headaches and how Rachel is constantly observing him in a highly suspicious fashion. There is also mention of a character named Rainaldi who may or may not be an accomplice in some dire plot against the ailing Ambrose.

Philip’s fears for the safety of his beloved cousin appear to be well-founded when he travels to Italy and learns that Ambrose has succumbed to a supposed brain tumor. The 24-year-old (who is heir to the estate in Cornwall) is understandably upset and believes there is more than a little substance to Ambrose’s insinuations regarding Rachel (‘Whatever it cost my cousin in pain and suffering before he died, I will return with full measure upon the woman that caused it’). But du Maurier’s book tossed us one of its telling moments of uncertainty here and the film faithfully adheres to the plot in this regard: upon his return to England, Philip is reliably informed that a death certificate confirms the aforementioned cause of death; moreover, Ambrose’s will has not been changed and so Philip stands to formally inherit everything on the occasion of his next birthday. A communication arrives soon after from the widow advising that she wishes to visit the home of her late husband. Reluctantly, Philip agrees to this, but is insistent that he remains dubious as to her intentions. As if to make this clear, he purposefully stays away from the house on the day of her arrival and orders the head man-servant not to serve dinner until he has come back. This rather ham-fisted attempt to establish his own authority comes crashing down when, upon his return that same evening, he learns that his cousin is already in her room and wishes to see him. Very soon, it is evident that Rachel has a certain aura about her which cannot be taken lightly and exerts a most striking influence.

But herein lies one of the main weaknesses of du Maurier’s original text as the clearly-smitten Philip quickly changes his tune and becomes little more than a lovelorn persona. All too soon, the young man is eager to please and berates himself whenever he causes a moment of awkwardness or makes an inopportune remark. The adapted script by Michell himself draws much on the theme of Philip’s general naivety as regards women and how Rachel might well represent a side of his manhood which he has not, heretofore, had the opportunity or inclination to indulge. The character’s inexperience is the occasion for her poking fun as she compares him to a puppy in one such instance; in another she teasingly enquires as to why he has not done the obvious thing and taken up with his pretty neighbour and lifelong friend Louise Kendall (Holliday Grainger). The plot thickens – or rather becomes a tad mawkish – as Philip decides to transfer Ambrose’s estate to Rachel. In the meantime, the possibly wily one has revealed how Ambrose did make a new will bequeathing her his worldly possessions, but, for some unknown reason, never got around to signing it. She is duly impressed when Philip makes such a gesture at midnight – as he turns 25 – and finally grants him access to her bed. Events turn somewhat sour, however, as Philip misinterprets what he perceives to be a marriage proposal acceptance. An ensuing pesky illness casts his mind back to those not-insignificant inferences from Ambrose’s letters. Rachel – who is now at a physical remove once again – insists that he drink her carefully-brewed teas. But are these a restorative or a poison we ask ourselves. Has the older woman one last dastardly scheme in mind? And what particular machination has the slippery Rainaldi in Cornwall all of a sudden? Is he a lover? Is he a lover and a co-conspirator?

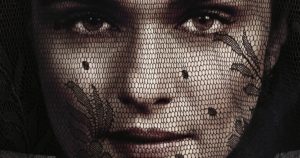

Much of the fun of du Maurier’s novel lies in the reader’s interpretation of character and design and Michell’s film leaves us with the suitably enigmatic ending as per the source material – ‘Rachel, my torment.’ The director arrives at the denouement in a slightly different manner to the book, but it’s actually more agreeable in terms of its dramatic punch and use of the Cornish coastline (did I just give too much away?). As to the film itself, one has to say that this is an expertly-mounted period piece which has a fine smattering of atmosphere – as a du Maurier story more than merits – and kudos should be directed the way of cinematographer Mike Eley, production designer Alice Normington and costume designer Dinah Collin. In the supporting cast, Game of Thrones’ regular Iain Glen does well as the thoughtful and paternally-minded Nick Kendall, as does the aforementioned Holliday Grainger playing his daughter Louise. This is Rachel Weisz’s show in the main and the Oscar winner demonstrates her considerable range once again playing a female protagonist who may simply wish to make her way in the world, or who might well be a conniving femme fatale par excellence. As Philip, Sam Claflin fares better than some reviews have suggested, but there is little in the way of sexual chemistry between himself and Weisz which detracts somewhat. As I mentioned earlier, I’m not quite sure what exactly has brought about this new screen version of the du Maurier book. The author – who died in 1989 (and whose centenary occurred in 2007) – still enjoys a deserved reputation to this day and any re-imaginings of her work are no bad thing in the humble estimation of this admirer. But My Cousin Rachel is not her best novel and the new screen version suffers somewhat from the plot and character inconsistencies which I have partly alluded to above. A welcome if, ultimately, imperfect entry as regards her oeuvre on screen.

Rating: C