The Greatest Story Ever Told – 10 Films You May Or May Not See At Easter

With the week that’s in it let’s take a look at 10 films that belong to, or have been strongly influential, in the biblical epic genre. Stories depicting events from the old and new testaments, or swords-and-sandals epics as they are often known, have been part of cinema since the silent era when filmmakers such as Cecil B. DeMille recognised the great scope they offered for expansive tales and panoramic vistas. As one of the early exponents of narrative cinema, DeMille himself made three biblical epics between 1923 and 1932 – The Ten Commandments, King of Kings and The Sign of the Cross. He re-made the most famous of these (The Ten Commandments) in the mid-1950s when the genre itself was in great vogue and moving perhaps towards its very pinnacle with William Wyler’s Ben-Hur at the end of that decade. In the 1960s the genre dropped out of favour somewhat as declining returns and audience attendances caused studio heads to rethink the prudence of producing such grandiose visions which often employed thousands of extras and oversized film sets. The genre came back into vogue somewhat in the early 2000s with the huge success of Mel Gibson’s dedicated, though often visually brutal, The Passion of the Christ. A recent re-imagining of Ben Hur was met with generally negative critical reviews and even poorer box office, but its very production nevertheless suggests a continued interest in this particular canon. One would not discount future remakes of such epics as The Robe or The Ten Commandments. Hollywood still loves its tales told on a grand scale and the biblical epic certainly provides such a template.

I’ve decided to pick out here 10 films that may well feature on television screens sometime over Easter. Two of the films are not biblical epics per se, but it can certainly be argued that they were produced, or at least greatly aided in their genesis (we’re talking biblical here remember), by the huge popularity of other such films at this time. The other eight listed are set, or centred, at the time of Christ’s ministry on earth. They feature the Messiah himself, or as a peripheral figure who significantly impacts on the narrative thrust of the stories being told:

Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy 1951)

The events depicted in this one occur in Ancient Rome from AD 64-68, and the main focus is on the conflict between the burgeoning Christianity and decadence of the Roman Empire. Robert Taylor plays a Roman military commander who falls in love with Deborah Kerr’s devout Christian. The circumstances of the times conspire against their love and bring them into direct conflict with the ever-so-slightly demented Emperor Nero (a suitably over-the-top Peter Ustinov). The burning of Rome is one of many fine set pieces in this film, but also watch out for the particularly memorable sequence in the arena involving Ursus and a certain wild bull. Elizabeth Taylor and Sophia Loren turn up in brief, uncredited parts. The film reputedly holds a record for the most number of costumes employed in one movie – 32,000 – and was shot on location in Rome and at the famous Cinecitta Studios.

The Robe (Henry Koster 1953)

This one is set squarely at the time of Christ and tells the story of a Roman military tribune (Richard Burton) who commands the unit responsible for the Messiah’s crucifixion. It’s a tad dated and not a little self-important in itself, but is quite splendid visually and was at the time the first film released in the new CinemaScope format. It also boasts a fine score from Alfred Newman. As with Ben-Hur, The Robe positions its central character in close proximity to the final days of Christ. Burton wins the robe at a game of dice beneath the cross and is beset by an overwhelming sense of guilt which leads to nightmares (and just a little bit of hammy acting by the famous Welsh thespian in the process). Unsurprisingly, there is a love interest involved (in the shape of Jean Simmons as Diana) and, of course, an implacable enemy (a virulent Caligula as played by Jay Robinson). The much underrated Victor Mature plays Burton’s devoted servant Demetrius. Having survived this particular film’s conclusion, Mature’s character would go on to star in a sequel Demetrius and the Gladiators released in 1954.

The Ten Commandments (Cecil B.DeMille 1956)

Cecil B.DeMille was in the twilight of his career when he made this one, but the old master still had it in spades when it came to making religious epics. This was a remake of the director’s own 1923 silent film and bear in mind that he also made other biblical films during this period – King of Kings (1927) and The Sign of the Cross (1932). This 1956 version – DeMille’s final film in fact – is most notable of course for its famous parting of the Red Sea scene (in full VistaVision splendour), but lets also appreciate the sheer scale of the production and all-star cast (Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson and Vincent Price amongst others). The film also firmly cemented the rising star that was Charlton Heston and he would go on to make an even more famous biblical epic a few years later. Heston had previously worked with DeMille on the director’s Oscar-winning The Greatest Show On Earth. He delivers a suitably stoic performance as Moses and is aided and abetted by the film’s historic locations including Mount Sinai. Financially, it remains one of the most successful films of all time, when adjusted for inflation, and, unsurprisingly, was the most expensive film made to that point in time. Be prepared for the length of it though – 220 minutes in total, including intermission. DeMille did not tend to make his films short.

Ben-Hur (William Wyler 1959)

Charlton Heston had more than established his credentials in this genre a few short years before with The Ten Commandments, and it seemed a natural progression that he should play Judah Ben-Hur in director Wyler’s remake of the 1925 silent film. If The Ten Commandments is most famous for its parting of the Red Sea sequence, then there is little doubt that Ben-Hur is most famous for its chariot race which took a full five weeks to shoot and required more than 200 miles of racing to complete. It remains one of the most potent sequences in cinema to this day, but lets not forget some of the other great set pieces in this film including the sea battle and the crucifixion. Based on Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, the film of course juxtaposes the life and fate of its central character with that of the Messiah. The adaptation was a painful one by all accounts and involved several writers including Gore Vidal and Christopher Fry. Whether or not there is a homoerotic subtext between Heston’s character and Stephen Boyd’s Messala still remains the subject of debate. Vidal later claimed that he persuaded Wyler to direct Stephen Boyd as if he were a spurned lover of Judah. He also claimed that Heston was kept in the dark about this. Wyler himself shot down such suggestions, but rumours still persist. The final screenplay was the subject of a bitter dispute over screen credits which subsequently involved the Screen Writers’ Guild. Karl Tunberg eventually got the sole credit. Winner of 11 Oscars at the time, Ben-Hur still holds the overall record along with Titanic and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Miklos Rozsa’s Oscar-winning score is still the longest composed for a single film. Watch out for the scene-stealing Stephen Boyd as Judah’s lifelong friend and sworn enemy Messala. Boyd – who hailed from Glengormley in County Antrim, and whose real name was William Millar – won a Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor, but, astonishingly, was not even nominated for an Oscar in the corresponding category (it went instead to one of his co-stars Hugh Griffith). His death scene, following the chariot race, is for me the outstanding moment of this film and one of the most unforgettable in epic cinema. ‘There’s enough of a man still left here for you to hate.’ Powerful acting indeed. And no, contrary to urban legends, no one died during the making of the nine-minute chariot race. Sam Zimbalist – the producer – did, however, die during filming from a heart attack.

King of Kings (Nicholas Ray 1961)

Nicholas Ray is probably most famous today for his 1955 teen angst drama Rebel Without a Cause (James Dean in his landmark role), but lets remember that he tapped into a number of genres during his career including western, film noir and, by way of this one, biblical epic. Jeffrey Hunter – John Wayne’s sidekick in John Ford’s iconic The Searchers – plays the Messiah here and the film chronicles events preceding his birth through to Herod the Great, the flight into Egypt, John the Baptist, and his own ministry. Notable for its emphasis on the political context of the Roman conquest, this film also devotes significant screen time to the characters of John the Baptist (played by Robert Ryan) and Barabbas (played by Harry Guardino). The film was shot in the Technirama process of the day and displays Ray’s visual penchant for contrasting wide panoramas of spectacle with more intimate, personal scenes. In contrast to the Christ figure in Ben-Hur (whose face is never actually revealed) Jeffrey Hunter is on prominent display as the central character. The late actor’s matinee-idol good looks caused some critics to derisively refer to this as “I Was a Teenage Jesus.” The film is far better than this put-down suggests and remains a very interesting entry in the overall canon. Rip Torn plays Judas Iscariot. Siobhan McKenna plays Mary. Orson Welles is uncredited as the narrator.

Barabbas (Richard Fleischer 1961)

Not one that readily rolls off the tongue when we speak of movies in this genre I will grant you, but it’s not devoid of its own curiosity factor. And it’s interesting as well that it was released the same year as King of Kings (as above) which also expanded on the character of the insurrectionary who is released by Pontius Pilate at the Passover feast. Directed by Richard Fleischer (20,000 Leagues Under The Sea and The Vikings) and produced by the legendary Dino De Laurentiis, this one takes its cue from the crucifixion of Christ and tells the story of Barabbas (Anthony Quinn) as he gradually becomes a believer and a man of action in the Christian struggle against the tyranny of Rome. Jack Palance plays the principal nemesis Torvald. Ernest Borgnine and Arthur Kennedy also feature in the cast. A previous version of the film was made in Swedish in 1953. The crucifixion scene is most notable as it was shot against the backdrop of an actual total eclipse of the sun which took place in February 1961.

The Fall of the Roman Empire (Anthony Mann 1964)

This one was more than an influence on the later Gladiator and effectively features Stephen Boyd (Livius) in the same role that Russell Crowe (Maximus) took in Ridley Scott’s Oscar-winning film. Christopher Plummer plays the treacherous Commodus and Alec Guinness is Marcus Aurelius. Interestingly enough Richard Harris – who subsequently played Aurelius in Scott’s film – was originally cast as Commodus, but was subsequently replaced by Plummer. Charlton Heston was also originally pencilled in for the part of Livius – he turned down the role when he heard Sophia Loren was to play Lucilla (the two had starred in Mann’s previous El Cid and, apparently, not hit it off). The film was a financial failure at the box office, but has been rightly reappraised with the passage of time. It was shot in 70mm Ultra Panavision and features the largest outdoor film set – the Roman Forum as reconstructed near Madrid. The Battle of the Four Armies set piece involved 8,000 soldiers, including 1,200 cavalry. The supporting cast includes such notables as James Mason and Omar Sharif.

The Greatest Story Ever Told (George Stevens 1965)

To say that this one had a tumultuous production history is a bit of an understatement. Director George Stevens (Shane, Giant, A Place in the Sun) became interested in Fulton Oursler’s 1949 novel whilst directing The Diary of Anne Frank. As part of pre-production, he commissioned over 300 oil paintings of Biblical scenes for use as storyboards, and also sought advice from the highest spiritual authority – no less than Pope John XXIII. Filming took place in the US; 47 sets were constructed; and principal photography – originally scheduled for three months – ran to over nine. One actor died, requiring his scenes to be re-shot, and the original cinematographer suffered a fatal heart attack on set. David Lean and Jean Negulesco were brought in to shoot additional sequences. By the time he finished shooting, Stevens had amassed a total of six million feet of film and the budget had swollen to 21 million US dollars. The film premiered in February 1965 to mostly mediocre reviews, but it is not without its supporters today. As with The Robe, I think it’s a little self-important and its length (260 minutes) does not readily facilitate a solitary sitting. Nevertheless, there is some marvellous photography to admire and the Oscar-nominated art direction is more than impressive. The most jarring thing about this film is perhaps the pop-up actors who appear during its marathon length. Although Stevens insisted on a relatively unknown actor in the central role (the great Max von Sydow was then best known for his work with Ingmar Bergman), he populated the supporting cast with very well-known Hollywood faces and A-listers. The most infamous of these was, no doubt, that of John Wayne. The Duke plays the Roman soldier who makes the famous pronunciation upon the death of Jesus. Apparently Stevens had the legendary actor do retake after retake of his solitary line ‘Truly, this man was the son of God.’ Watch out for his familiar silhouette on the hill of Calvary. His gravelly voice is unmistakeable. Biblical epic veteran Charlton Heston also turns up playing John the Baptist.

The Last Temptation of Christ (Martin Scorsese 1988)

Hugely controversial on its initial release (the departure from the Gospels narratives and the scenes in which Jesus lives out a full secular life and, consequently, enjoys the pleasures of the flesh), this one sparked protests from several Christian groups who organised boycotts and other protests. Like the novel of the same name, Scorsese’s film presents us with a Christ who is struggling with the weight of his own destiny and with various human emotions such as fear and desire. Scorsese as a director had tackled such weighty themes in some of his previous films – perhaps, most notably, Mean Streets, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull – and he also confronts in this the matter of his own Catholic background and how it informed his development as both an individual and filmmaker. Scorsese himself had expressed over the years a keen interest in the biblical epic. He has referenced Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings in particular as being an influence upon him, and really it should have come as no great surprise that he would make his own film in this genre. Interestingly, there was an aborted 1983 production which was set to go before the cameras until Paramount pulled the plug. Aidan Quinn was originally cast in the main role; Sting was slated to play Pontius Pilate. This version, which eventually reached screens in 1988, has Willem Dafoe as Christ and David Bowie as Pontius Pilate. Other cast members include Harvey Keitel as Judas and Barbara Hershey as Mary Magdalene. The film’s soundtrack was composed by Peter Gabriel. Scorsese received an Academy Award nomination for Best Director.

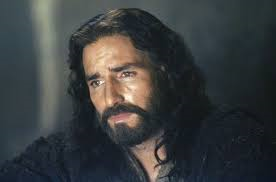

The Passion of the Christ (Mel Gibson 2004)

Mel Gibson scored box-office gold with this one from behind the camera. A budget of 30 million US dollars returned 612 million approximately worldwide making it the highest grossing religious film of all time, the highest grossing non-English film of all time, and (as of this moment) the most successful R-rated film in America. Gibson focuses on the last 12 hours of Jesus’s life (with some flashbacks from his childhood) and employs Aramaic, Latin and Hebrew as the mediums to tell his story. The Passion of the Christ is based on the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John and was shot in Italy (mostly at Cinecitta Studios, and also on location in Southern Italy). Not surprisingly, the film polarised audiences and critics on it release. Unlike Temptation, it received huge support from the American evangelical community, but many questioned the excessive violence which is a predominant aspect of the film. Personally speaking, I have only seen this film once (when it was first released), but I can honestly say that I would never be able to bring myself to a second viewing. The film has its merits in its splendid cinematography, and a fine central performance by Jim Caviezel, but, hand on heart, I have to say it is one of the most brutally violent films I have ever seen (I’m thinking in particular here of the scourging scene). Gibson defended his work at the time saying that he wanted to offer a realistic depiction of what such torture and crucifixion would have been like. He also said that he wished to emphasise the sacrifice made by the Messiah. The unfortunate thing is that the message of the Passion is too often undermined by its relentless cruelty and bloodshed. If you haven’t seen it, approach with caution; it’s most definitely not for the squeamish. A slightly edited version (omitting five minutes of the most explicit violence) was released in 2005 under the title The Passion Recut.