‘We rob banks!’ – 50 Years of Bonnie and Clyde

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde celebrates the 50th anniversary of its release in August 2017. Starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway as the titular characters, this is a film which remains vital to this very day and is quite rightly regarded as marking a significant shift in Hollywood cinema. Telling the story of the unlikely couple who pulled off a number of bank robberies across the Midwest and South of America in the early 1930s, Bonnie and Clyde was – and still is – notable for the style and tone it employs with respect to its themes and visual aesthetic. Controversial in some quarters for its supposed glorification of murders and its attendant bloodletting, the film did not hold back with respect to its depiction of this subject matter. Its ending, of course, is one of the most famous in all of cinema and – in terms of style – influenced subsequent pictures such as Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Coppola’s The Godfather. Nominated in its day for 10 Academy Awards (it won just two for Best Supporting Actress and Best Cinematography), Bonnie and Clyde’s classic film status has long since been secured ranking as it does as the 5th best gangster film of all time on the American Film Institute’s list; and also 27th on the AFI’s overall list of Best Movies. The line ‘We rob banks’ is generally recognised as one of the most famous movie quotes. This ground-breaking film enhanced the careers of Warren Beatty (who also served as the producer), Faye Dunaway and Gene Hackman. It also introduced Gene Wilder and brought the likes of Michael J. Pollard and Estelle Parsons to greater screen prominence. Co-screenwriter Robert Benton went on to direct films such as Kramer vs. Kramer, Places in the Heart and Nobody’s Fool. In his review of the film on its initial release in 1967, the late film critic Roger Ebert hailed Bonnie and Clyde as, ‘a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance.’ In that same critical analysis he also made the telling suggestion that, ‘Years from now it is quite possible that Bonnie and Clyde will be seen as the definitive film of the 1960s, showing with sadness, humour and unforgiving detail what one society had come to.’ As we look back on this landmark in American cinema, we are pleased to say that Ebert’s words were indeed most prescient.

Not just another genre picture:

The fact that Warner Bros.-Seven Arts did not exactly support the film or subsequently market it in any meaningful way is well documented. The ageing studio head Jack L. Warner almost immediately regretted his decision in green-lighting the film and remarked upon how, ‘This era went out with Cagney.’ A famous story oft-told has Warren Beatty kissing the movie mogul’s feet in a desperate attempt to get him to finance the small-scale gangster flick. Beatty is adamant he never lowered himself to such an act, but his powers of persuasion – whatever they were – worked like a charm. Nevertheless, Warner and many others remained unconvinced to say the least. The film’s location shoot in Texas – ‘far from the heavy hand of the studio’ as film historian Peter Biskind puts it – was to its general advantage as, in truth, it has none of the familiar trappings of the gangster genre to that time. This was readily apparent in the opening scene in which Bonnie spots Clyde outside her house as he contemplates stealing her mother’s car (‘I was in state prison’ he informs her in an obvious boast). The viewer has just seen snapshots from the Depression Era over the film’s opening credits and Penn’s direction keeps us firmly placed in this time period. Much has been made of the sudden shifts in the film’s tone and tempo. At first we imagine we are witnessing two bungling miscreants who can barely hold up a shop, let alone a bank – I reference here in particular the convenience store scene in which Clyde is resisted by a shop assistant bearing a meat cleaver. The same semi-comic streak is palpable when the inexperienced C.W. Moss parks the car on his first job and is later berated by Clyde. But Clyde has been forced to shoot a bank employee in the face and it hasn’t been pretty. The fluctuations continue right up to that climactic ambush which I will refer to later. Writers Robert Benton and David Newman – who were inspired by a book called The Dillinger Days by John Toland – cited the key influence the French New Wave had on their approach. Such is also the case with Arthur Penn’s direction with its sudden changes of tone and disjointed editing.

David Newman would later go on the record saying, ‘The thing we loved about Bonnie and Clyde wasn’t that they were bank robbers, because they were lousy bank robbers. The thing about them that made them so appealing and relevant, and so threatening to society, was that they were aesthetic revolutionaries.’ Jack L. Warner, however, did not agree. When he first saw the film, the Warner Brothers kingpin hated it with a vengeance. Producer Beatty tried gamely to explain its premise and purpose describing it as a, ‘homage to the Warner Brothers gangster films of the 30s.’ Warner’s response to this was both cutting and succinct – ‘What the fuck’s a homage?’ he tersely enquired. The studio which had pioneered ‘talkies’ in the 1920s effectively attempted to bury the film with a September 1967 theatrical release which was tantamount to consigning it to oblivion. But Beatty did not give up and fought for more lucrative dates. Inviting many of the greats of the cinema world to a special screening at the Old Directors’ Guild Building in Los Angeles, the actor heaved a great sigh of relief as the film enjoyed an ecstatic response. Bonnie and Clyde had its worldwide premiere at the Montreal International Film Festival at Expo ’67 on the 4th August, 1967 (its general release date was the 13th August, 1967). A standing ovation ensued and there were fourteen curtain calls. Business was middling initially and some of the contemporary reviews were derisive. The famous New York Times critic Bosley Crowther lambasted it unceremoniously, but there were others – such as the up-and-coming Pauline Kael – who rushed to its defence. Penning a nine-thousand-word piece, which made the pages of the New Yorker, Kael compared it to John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate and declared that, ‘The audience is alive to it.’ It was a turning point in the film’s fortunes, but, perhaps, of far greater import was an 8th December 1967 Time Magazine cover which featured Bonnie and Clyde and was accompanied by an article titled ‘The New Cinema…Violence…Sex…Art’ by Stefan Kanfer. Writing about the emerging trend of new cinema in America, Kanfer posited a seismic departure in which time-honoured concepts such as plot, chronology and character motivation were dispensed with and replaced by a more innovative European approach. Elements such as ambivalent heroes and villains, sexual promiscuity and oscillating moral codes were becoming the norm. Bonnie and Clyde perfectly represented such an evolution. Time named it the best movie of the year and Beatty used such favourable attention as leverage to have the film re-released. The so-called genre picture would go on to become a genre-defying classic.

The producer and star – Warren Beatty:

Beatty was dating Gigi star Leslie Caron when he first heard of the script by Benton and Newman. Dining in Paris with his then-girlfriend and French film director Francois Truffaut, the actor (probably best known to that point for 1961’s Splendor in the Grass) badly wanted a vehicle to put himself in the spotlight and on a par with the very best actors of his generation. Once back on American soil, he contacted Benton and arranged to pick up the script some twenty minutes later. In spite of having certain reservations (particularly with respect to the menage a trois sub-plot), Beatty decided the project was for him and optioned the screenplay for $7,500. Initially, he was unsure if he would take on the role of Clyde and imagined Bob Dylan for the part. As regards a director, the two screenwriters suggested Arthur Penn with whom Beatty had previously collaborated by way of 1965’s Mickey One. Penn hemmed and hawed, but eventually accepted the job. Bonnie and Clyde was Beatty’s first film as a producer and the responsibility and experience had a telling effect on his subsequent career. Known to be a perfectionist himself behind the camera, Beatty questioned practically every decision made by Penn and the two clashed on a daily basis by all accounts. But there was a meeting of minds as well and the director and producer agreed on the nature and visual style of the violence which they wished the film to depict. As Penn put it, ‘It used to be that you couldn’t shoot somebody and see them hit in the same frame, there had to be a cut. We said – let’s not repeat what the studios have done for so long. It has to be in your face.’ This is most certainly a film which is in your face from the get-go and one of its most memorable aspects is that of Beatty’s own performance on screen. Brash and boastful at first, there is also an unmistakable vulnerability regarding his failure to sexually perform (‘I ain’t much of a lover boy’) which Beatty nails in that inimitable way of his. ‘You may be the damn best girl in Texas,’ he tells Bonnie as he sells her the possibility of a better life in which she can enjoy the finer things. Let’s not forget that this is the era of the Great Depression – such fame and fortune, albeit it by lawless means, is what the young woman has been pining for.

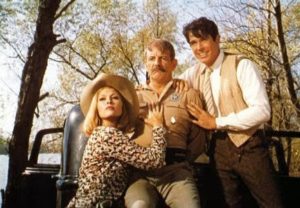

The very next morning Clyde teaches her how to shoot and Bonnie takes to it like a natural. The family who are being forced to move out of the abandoned house in which they’ve spent the night tell the couple of their woes. ‘Bank took it,’ the father informs them. In an apparent gesture of fraternity, Clyde encourages him to shoot the bank notice at the house and then the windows as well. ‘We rob banks,’ he adds with a knowing grin as introductions are exchanged. One of my own personal favourite scenes of Beatty’s in this film involves him and Gene Hackman (Buck Barrow) as the brothers are reunited. There’s a lot of masquerading and backslapping and Buck – of course – asks if Bonnie is as good as she looks. Clyde lies in his response and the play-acting continues with Buck declaring that they are going to have themselves ‘a time,’ before simply inquiring, ‘What we gonna do?’ I also like Clyde’s reaction when the Texas Ranger Frank Hamer (Denver Pyle) spits in Bonnie’s face after they have mocked him and taken his picture. ‘We got you now! We got you now!’ he yells as he puts the tied-up lawman into a boat on the river. All in all, Beatty deserved full kudos for doubling so effectively on this picture on both sides of the production. Without his tenacity and belief, the picture might never have got made. Without his charismatic performance, the film would not be nearly as absorbing or as endearing.

A palpable change in style and tone:

Peter Biskind points out that, ‘By making villains of traditional authority figures – bankers, cops, parents – Bonnie and Clyde went considerably further, turning conventional morality on its head. The film legitimated violence against the establishment, the same violence that seethed in the hearts and minds of hundreds of thousands of frustrated opponents of the Vietnam War.’ 1960s America, as we well know, witnessed many societal changes and its cinema-going public were eager for artistic innovation to reflect and endorse such dynamics. The golden age of Hollywood – as it was known – had drawn to a close and younger audiences had little time for the epics and musicals which had been such a feature and mainstay of the 1950s and early 1960s. They voted with their feet and stayed away from the likes of Doctor Dolittle and Paint Your Wagon. The production excesses of 1963’s Cleopatra were similarly well known. Despite being the highest grossing film of that year, the historical epic starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor ended up making a loss owing to its inflated costs. The counter-establishment mood which Bonnie and Clyde exemplified appealed greatly to a nation which felt vibrant, young, but, crucially, angry with the powers-that-be. This was a powerful combination of factors and it demanded change in movie-making practices as much as it did in social and political spheres. No longer was there a place for the unambiguous hero who has a definite moral code and a straight way of living. The Henry Fondas and John Waynes of this world no longer held sway or enjoyed the sort of influence they had heretofore. Fonda acknowledged as much in his portrayal of Frank in Sergio Leone’s epic Spaghetti Western Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Wayne was far less pliable, sticking to his conservative principles on and off the screen. He was, for example, deeply dissatisfied with Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973) and wrote to the actor-director to air his grievances. But the dye was well cast at this stage. New Hollywood was very much in vogue. Directors such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Hal Ashby and Robert Atman were on the rise. The rules of the old Hollywood mattered little to them. Intent on forging their own visions, they settled on new styles and attitudes that were very much a departure in American cinema. The bad guys, the murderers and criminals became the focal point of many films in the 1970s. Released just a few years prior to the beginning of that seminal decade in cinema, Bonnie and Clyde blazed a trail. It was the start of a cinematic revolution. Unashamedly, it broke with convention and inclination. It also posited the traditional authority figures as the real malefactors.

This latter theme is most apparent in the final act of the film as far as I’m concerned. Following a bloody shootout in the woods which has claimed the life of Buck and led to the capture of Blanche, Bonnie and Clyde (also injured) accept shelter at the home of C.W.’s father Ivan (Dub Taylor). The latter is not so much surprised by the appearance of the infamous outlaws, as he is disgusted by the sight of his son’s tattoo – ‘You look like trash all marked up like that!’ The father believes he knows best and determines on striking a bargain with Hamer who has managed to trick Blanche into giving up C.W.’s name. The trap for the couple is duly set and Ivan plays an active part in this by staging a flat tyre on the side of the road. When the climactic moment comes, he ducks underneath the vehicle. Hamer and his posse similarly conceal themselves behind bushes, emerging only when the execution has been carried out. Parents and police have conspired to bring their activities to a shuddering halt. Thematically and in a narrative sense, Penn’s film has nowhere else to go and so ends as the forces of law and order stare upon the bullet-ridden bodies.

Sex and violence – the breaking of cinematic taboos:

From the time he optioned Benton and Newman’s script, Warren Beatty had serious reservations concerning the menage a trois aspect to the story as it related to Clyde, Bonnie and C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard) – ‘Let me tell you one thing right now,’ he is quoted as having said, ‘I ain’t gonna play no fag.’ Arthur Penn was especially instrumental in bringing the writers around to the idea of dropping this particular plot point and it was decided to render Clyde impotent instead. The opening scene has a naked Bonnie in her room as she lies on her bed in an obvious state of boredom. The appearance of a good-looking rascal outside is a boon to her sexuality and we note how quickly she comes out to him and overlooks the fact that he has been attempting to steal her mother’s car. Bonnie’s sexual lust is on a par with her desire to break with her small-town Texan mould and this is altogether apparent as she strokes Clyde’s gun and then dares him to use it. Following the subsequent grocery store hold-up, we see just how sensually-oriented Bonnie is, but Clyde dampens this immediately with his non-response – ‘I ain’t much of a lover boy.’ The criminal act is, of course, Clyde’s way of performing for Bonnie for much of the film. When an early bank job (in a bailed bank) yields no money, Clyde brings the bank teller out to the car to explain this to Bonnie. Although he cannot satisfy her sexually, the amateurish robber is nevertheless mindful of his manhood. Bonnie must be made aware of the reason for his failure on this occasion and she must realise that he has and is doing his utmost.

The bloodshed which must inevitably accompany such a spree is in evidence soon enough as Clyde is forced to shoot a bank employee in the face. This is one of the instances in the film which Penn spoke about when he referred to shooting somebody and seeing them hit in the same frame. The violence on display here is very much ‘in your face’ as he put it. Clyde himself certainly thinks so because he offers Bonnie the opportunity to get out now that he has killed a man. ‘At least I ain’t a liar. I told you I was no lover boy,’ he tells her after he disappoints her once again in the bedroom. The introduction of Buck and Blanche make Bonnie all the more restless as she scorns the idea of some perverse notion of domestic bliss -‘There is always somebody in the next room,’ she complains as Clyde asks her to quieten down her mocking of Blanche. A field of hay some time later is similarly the occasion for such a criticism as she remarks on his, ‘peculiar idea of love-making, which is no love-making at all.’ Bonnie’s proclivity towards sex is overt and we understand her attendant frustrations. Clyde we also empathise with because, in the absence of achievement in this field, he feels the need to conquer and impress by other means. Sex and violence had seldom been so closely associated up to this time in American cinema. The characters of Bonnie and Clyde speak openly about it, venting their discontents – even vexations – to varying degrees. It was a liberating moment which allowed subsequent films such as Polanski’s Chinatown to further expand on themes which once were deemed immoral and indecorous.

The sense of an ending:

The sequence in which the gang playfully take Eugene Grizzard (Gene Wilder) and Velma Davis (Evans Evans) hostage is certainly one of the more humorous of the film, but the mood changes markedly – at least from Bonnie’s point of view – when he reveals that he is an undertaker. ‘Get them out of here,’ she immediately demands and the couple are duly left stranded on the side of the road. This is a turning point in the film as it reminds the gang (and the viewer for that matter) that their days are numbered and will most likely end in a hail of bullets. Admirers of the film and movie critics have pointed to a subsequent scene for such an alteration in tone, but it begins with this one in my estimation. Some time later, a distraught and homesick Bonnie tells Clyde that she wishes to see her elderly mother. Aware that her house is under surveillance, they meet in a neutral venue along with other members of her family. Clyde – being Clyde – sweet-talks Mrs. Parker, but the practically-minded and straight-talking woman does not mince her words as regards their prospects – ‘You best keep running Clyde Barrow and you know it.’ When Bonnie tentatively suggests that one day she might move back closer to her hometown, the response is equally as forthright – ‘You try to live three miles from me and you won’t live long honey.’

The famous climactic ambush at the film’s end – referred to as the Jack Kennedy scene – has its justifiable reputation and was shot by four cameras going at different speeds. Beatty termed it, ‘as violent a piece of film as ever had been in movies.’ To that point in time this was probably the case, but The Wild Bunch’s infamous Agua Verde gun battle sequence some two years later goes even further with respect to its visual impact and grotesque detail. Nevertheless, Bonnie and Clyde’s bloody conclusion has its place in cinema history and cemented the film’s iconic status. In terms of set-up, technique and execution, it still leaves quite an impression to this very day. One of the first films to make extensive use of squibs, it’s a raw and gory denouement which is heightened by the almost surreal movements of Beatty and Dunaway’s bodies as they are riddled by bullets. Balletic ballistics if you will.

Legend and legacy:

‘We didn’t know what we were tapping into. The walls came tumbling down after Bonnie and Clyde. All the things that were in concrete began to just fall away.’ – Arthur Penn

Bonnie and Clyde deserves its place and reputation in American cinema because it spearheaded a trend within the industry which was more audacious and less time-honoured. The film’s influence cannot be doubted, nor can its impact upon a society and art form that was crying out for the new and the less conventional. It had a real originality despite being set and predicated in a genre which seemed too familiar for some. The likes of Jack L. Warner and Bosley Crowther got it wrong when they viewed it as just another gangster flick and a hackneyed piece. Even Roger Ebert could not guess at how accurate his words were to prove when he hailed it as, ‘the definitive film of the 1960s.’ Fellow critic Pauline Kael probably came the closest because she gauged it with respect to the audience’s reaction. The movie-going public who flocked to see it on the occasion of its deserved re-run ensured the success and reputation of the film. Bonnie and Clyde was a perfect vehicle for the jaded Vietnam era – one of its most abiding and straightforward messages was that the establishment is not always right and should, therefore, not be held up as the paragon of reason and good sense; sometimes the so-called good guys are much much less than good. The criminals and counter-establishment figures may have a tenable argument it tells us; their motivations are not entirely self-serving. Finally, I refer to one of the film’s final moments and, arguably, the most tender exchange between Bonnie and Clyde. Reading aloud the poem she has written and published in a newspaper, titled The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, the female protagonist is praised by her partner who remarks, ‘You know what you done there? You told my story. You told my story right there, right there. One time I told you I was gonna make you somebody, that’s what you done for me. You made me somebody they gonna remember.’ A perfect example here of legend and legacy in close proximity. A film they gonna remember for all time.

Nice tribute.

Thanks Elaine!!