‘What we’ve got here is failure to communicate’ – 50 Years of Cool Hand Luke

Cool Hand Luke starring Paul Newman (as the titular character) and George Kennedy (in an Oscar-winning performance), celebrates the 50th anniversary of its release in November 2017 and we look back fondly on an iconic prison-based drama that has been rightly hailed as one of the best anti-establishment films of the 1960s. Filmed mostly on the San Joaquin River Delta and in Stockton, California, and based on the novel of the same name by Donn Pearce, Cool Hand Luke tells the story of one Lucas ‘Luke’ Jackson, a decorated war veteran, who is sentenced to two years in prison for a petty crime. The exact reason for Luke’s actions prior to his sentencing and incarceration are never exactly established in director Stuart Rosenberg’s film, and we can only suppose that it is on account of a disaffected and rebellious streak which informs the central character. Events which subsequently unfold certainly suggest his dislike for authority. And there is no mistaking the lengths to which he will go to display his rejection of rules and regulations.

The opening scene in which Luke is introduced to us belongs to the familiar face of Paul Newman and his trademark grin. In a state of intoxication, he has decided to engage in a blatant act of vandalism – cutting the heads off parking meters. But instead of fleeing the scene of the crime, as any normal malefactor might do, Luke chooses to sit on the pavement to seemingly await the forces of law. Is this a deliberate decision on his part? The answer I think is yes. The grin which flashes as lights are shone in his face serves to confirm as much. Luke may be inebriated, but he also appears to understand what may lie in store for him. Perhaps he has reached some vague point of hopelessness. Some of the character’s later musings in the film suggest that he feels he has no proper place in the world. Sentenced to a Florida chain gang prison, Luke is introduced to the rather humourless Captain (played by Strother Martin). The new inmates who also figure in his group include the likes of Harry Dean Stanton and Ralph Waite. Other recognisable faces who turn up among the general body of prisoners are Dennis Hopper and Wayne Rogers. Luke immediately sets himself apart from the others as he cynically remarks on all the ‘rules and regulations.’ The prisoners’ leader Dragline (George Kennedy) takes an immediate dislike to the younger man. Who is this upstart shooting off his mouth on the very first evening? Dragline feels threatened because he sees Luke for what he is and also recognises his irrepressible spirit. It’s not long before he’s remarking on Luke’s war record which, apparently, is impeccable. The truth of the matter is that Dragline and the other prisoners have been waiting for a Luke-type character, a bona fide hero. The tension and distrust which prevails early on is fleeting in nature. Very soon Luke’s name will be the stuff of legend among them. By various acts of defiance and rebellion, he will come to epitomise what they can only aspire to be.

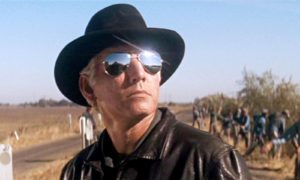

Famous film critic Roger Ebert commented on the pessimistic tone he saw running through the course of the film when he revisited it for his Great Movies series. It’s true that Cool Hand Luke is not a light film, but there are some moments of levity which are provided by Rosenberg and scriptwriters Donn Pearce and Frank R. Pierson. The famous (and much imitated) scene in which a scantily-dressed blonde woman (Joy Harmon) lovingly soaps a car in front of the chain gang is one such moment. Referring to her as Lucille for no obvious reason, Dragline articulates a sentiment that the other men are feeling in their loins – ‘Hey Lord, whatever I’ve done, don’t strike me blind for another few minutes.’ The famous egg eating bet also has a tinge of humour to it and we will come to that in due course. The boxing match which takes place between Luke and Dragline is a significant scene in that it is a game-changer with regard to the men’s opinion of him. Hopelessly outmatched and severely pummelled by his much larger opponent, Luke simply refuses to lie down and take a beating. ‘Stay down,’ the other men implore him. Seeing that Luke will only give up at the point of death, Dragline himself quits the circle. It’s a victory of sorts for the main character and his stock quickly rises in the community. Luke earns the nickname ‘cool hand Luke on account of his proficiency at poker. The others, including Dragline, look up to him now. The growing respect, near-adulation, directed his way is not lost on the Captain and the bosses, particularly Boss Godfrey (Morgan Woodward) – the ‘man with no eyes.’

The film’s most touching scene for me occurs when Luke receives a visit from his sick mother Arletta (Jo Van Fleet). Laid out in the back of a truck and puffing laboriously on a cigarette, we can deduce how she realises that this is the last time she will ever see her son. Luke is painfully aware of this fact as well. ‘You ain’t alone. Everywhere you go, I’m with you,’ she tells him whilst also acknowledging the fact that she will probably be dead by the time he is released. An air of finality hangs over this pivotal scene which is beautifully played by both Newman and Van Fleet. In direct contrast to this is the note of dismissal Luke’s brother John strikes as he curtly hands him a banjo – ‘Now there ain’t nothing to come back for.’ This is one of the final separations between Luke and the outside world. Quite soon, he will have no family to speak of; not in the conventional sense at least. The realisation that his familial connections are fading fast appears to spur Luke on as he inspires his fellow inmates in the memorable road-paving scene. This is a culmination of unity and camaraderie, but it does not best please the Captain or his bosses. The famous egg eating scene (in which Luke manages to down fifty hard-boiled eggs in one hour) is probably the film’s most famous sequence concluding, as it does, with a Jesus-like shot of Luke as he lies sprawled across a table. Much has been made of such imagery and allusions which run through the course of the film. Idolised and idealised as he is by the others, Luke will also come to remark upon the heavy burden he has to bear. He will be physically punished, verbally abused, emotionally intimidated and even, for a time, abandoned by his so-called friends.

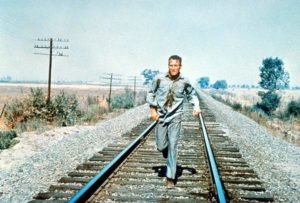

A turning point in the film – and in Luke’s personal fortunes – comes as he is informed of his mother’s passing. Fearing that the news might cause Luke to escape in order to attend the funeral, the insensitive Captain decides to take him off the road for a time and has him placed in the box – a confined space normally reserved for punishment. Unsurprisingly, this has quite the opposite effect – on the Fourth of July – a rest day – Luke breaks out and cleverly throws the pursuing dogs off his scent. Recaptured after a short time, Luke is returned to the chain gang where he is made an example of by the Captain – ‘What we’ve got here is failure to communicate. Some men you just can’t reach. So you get what we had here last week. Which is the way he wants it. Well, he gets it. And I don’t like it any more than you men.’ Undaunted, Luke soon escapes again, this time putting the guard dogs off his scent with curry and chili powder. His period of time on the run is much longer than the first and Luke takes the opportunity of mailing Dragline a magazine which includes a picture of him with two beautiful women. Having previously observed the effect the blonde woman had on the prisoners, an argument could be made here that this is a form of teasing on Luke’s part. He surely knows what he is doing. He knows full well the elevated position he holds in their minds, most especially Dragline’s. Is it a moment of narcissism on his part we have to ask ourselves. Is the exalted one deluding himself with notions of grandeur and self-importance?

The latter would seem to be the case upon his recapture and subsequent return to the prison. Revealing that the photo in question was essentially a sham, Luke turns on the others for placing him on a pedestal – ‘Stop feeding off me!’ Broken and dispirited, Luke is punished for his attempted escape by a long spell in the box and is taunted by the relentless bosses. The culmination of their goading and persecution occurs when he is forced to repeatedly dig a grave-sized hole in the camp yard. Exhausted and apparently beyond his breaking point, Luke finally collapses into the hole and begs for mercy. The fickleness of his fellow prisoners (akin here to the Roman mob) is perfectly captured as one of them tears up the much-revered photo of him and the two women. As he struggles to get into his bunk that same night, a despondent Luke angrily reflects on how quickly they have turned their backs on him – ‘Where are you now?!’ he yells as they pointedly refuse to help him in his moment of need.

Realising – as I would suggest – that he has lost the faith and devotion of his supporters, and unwilling to play sycophant to the bosses, Luke breaks free one last time as he flees in a truck from the roadside with Dragline in tow. Having camouflaged the vehicle, Luke proposes they should go their separate ways much to the disappointment of the older man. The church scene which follows plays something like the Garden of Gethsemane and, again, comparisons have been put forward by critics and film scholars in this regard. The suggestion by some that Dragline is the equivalent of a Judas Iscariot here is a misconception by my reckoning. He re-appears in the church telling Luke that the bosses, dogs and sheriffs are outside and that he has come in to talk into surrendering. When the forces of authority outside renege on their word by shooting Luke, Dragline is visibly outraged. Attempting to strangle Godfrey for this, the big man is overpowered by the others. It’s not the action of one who has betrayed his friend I think, but rather the stark realisation that he has been used by the Captain and bosses in their design. There are no thirty pieces of silver involved in this. Dragline’s motivation – I would suggest – is to save his friend because Luke, in truth, has nowhere else to go. His conversation with God in the church just prior to this is illustrative of this point – ‘What you got in mind for me? What do I do now?…I guess I’m pretty tough to deal with, huh? A hard case.’

Badly wounded from the gunshot, Luke is driven away to the prison hospital as opposed to the nearby one on the instructions of the Captain. It’s absolutely clear that he does not want this insubordinate prisoner to survive as he dismisses the protestations of the local police. Luke’s eventual fate is not explicitly revealed at the film’s end, but we can infer his death as Dragline speaks of him in the past. His tone is laudatory, of course, in keeping with much of the film. There is more than a hint of myth-making as he fabricates about Luke having that ‘Luke smile’ on his face as he was driven away from the church. This we know was not the case. But it’s important to Dragline to propagate the legend of Luke as much as it is for the other prisoners to believe him. Luke is now a martyr to them. He has died because he remained his own man, because he refused to conform, because he was never willing to bend.

This is one of Paul Newman’s most celebrated roles and his central performance (described as ‘one of the most indelible anti-authoritarian heroes in movie history’) is the fundamental component which makes Cool Hand Luke work as well as it does. Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor (he lost to Rod Steiger for In the Heat of the Night), it’s difficult to imagine anyone else but Newman in the part. His Luke is hugely complex – suave and confident, but also vulnerable and restless. My own personal favourite scene in the film – as I’ve hinted – is that of the deeply felt exchange between him and Jo Van Fleet. There are very few scenes in modern-day cinema which are as powerfully played as this one. The simple fact of the matter is that Newman should have won the Oscar for this film – as it turned out he had to wait almost another 20 years before finally triumphing in the category for Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money. George Kennedy, as I mentioned, did win an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his memorable Dragline; Pearce and Pierson were nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay and Lalo Schifrin was nominated for Best Original Music Score. 50 years on from the time of its theatrical release, Cool Hand Luke is as fresh and as vital as ever and it benefits from its stellar cast, solid direction by Rosenberg, excellent script, catchy score and superb cinematography by Conrad Hall. The spirit of Luke’s indomitability rests at the core of the film, but there is also a marked examination of other themes such as excessive glorification and the responsibilities of the individual to the group and the group to the individual. On the subject of courage, it should come as no surprise that the American Film Institute’s 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains list places Luke at number 30 in terms of heroes. The same organisation’s 100 Movie Quotes list places the line ‘What we’ve got here is failure to communicate,’ at number 11. Like the famous quote itself, Cool Hand Luke continues to this day to enjoy lasting popularity and deserved esteem. What we’ve got here is most definitely a classic movie.

Great film. Damn fine write-up.

Thanks Bill! Much appreciated!